Alternative voice: inclusive decision-making empowering Dundee’s community

What key aspects and principles make this community's participatory approach successful? Dundee people with lived experience of poverty share their thoughts.

1. Introduction

Amplifying the voices of people with lived experience of poverty is critical to finding policy solutions to reduce poverty and increase equality. Support for community participation in anti-poverty policy design in Scotland has grown significantly in the last decade. This is partly due to the Scottish Government (2015) legally recognising the need for greater participation in public decision-making (McKendrick, Marchbank and Sinclair, 2021). While there is broad agreement that policies should be designed with the involvement of those who will experience them, there is work to be done on how to meaningfully engage people in practice.

This briefing follows the story of Dundee Fighting for Fairness (DFFF), a group of Dundonians with lived experience of poverty who have developed a strong working relationship with Dundee City Council and the Dundee Partnership through the Dundee Fairness Leadership Panel (DFLP). Together, they have successfully worked to change the way decisions are made, strengthened inclusive communication strategies and developed effective anti-poverty initiatives.

2. People involved in a new approach

JRF has provided financial support to Faith in Community Dundee (FiCD) to enable the development of DFFF. Following this, over the last 9 months, we spent time talking to members of DFFF, FiCD, the DFLP and other service delivery decision-makers to explore the key successes and learnings of the work. We interviewed 19 people, encouraging them to reflect on how the balance of who participates in conversations about poverty and financial security has shifted.

The aim of this briefing is to share the success and learnings from the unique model of participation that has evolved in Dundee. The evidence from this research shows that valuing and investing in collaborative approaches to tackling poverty that centre people with lived experience results in strengthened relationships between decision-makers and the community, and effective policy design.

Dundee Fighting for Fairness

DFFF is a group of Dundonians with lived experience of poverty who have been working collaboratively with Dundee City Council and other service delivery decision-makers to ensure that the voices of people who often go unheard are instead amplified in these spaces.

FiCD supported DFFF in evolving out of its prior work with the Dundee Fairness Commissions, which ran between 2017 and 2021. The Fairness Commissions brought together community commissioners (people with lived experience of poverty) and civic commissioners (people with the power to make changes) to provide insight, from a range of perspectives, into the inequality and financial insecurity experienced by people in the city. After the success of the Commissions, DFFF was established as a core group – later gaining charitable status – that provided an independent space for people to strengthen their commitment to advocating for positive change.

DFFF acts as an important link between the community and people in positions of power who design policies that impact the lives of those facing poverty and inequality. Crucially, it works in partnership with other community groups and public services to understand more about the issues people are facing and collaboratively think about solutions before engaging in discussions about how they can make these changes happen.

Dundee Fairness Leadership Panel

DFFF’s continued partnership with Dundee City Council led to the opportunity to solidify this relationship with a new initiative, the Dundee Fairness Leadership Panel (DFLP). The model of DFLP grew out of the success of the more well-known commission model. In many ways, DFLP works like a commission. It brings together members of DFFF and decision-makers to address poverty and its drivers. Crucially, it includes a range of key players, including the Chief Executive and Leader of the Council, service delivery managers and officers, and wider public sector professionals. However, there are some differences in its structure and principles, particularly as the DFLP is an embedded long-term panel rather than a short-term commission. Later in this briefing, we will discuss how the structure and principles of the model have created the conditions for success, enabling meaningful action and policy change.

A participatory approach to fairness

Dundee has taken a collaborative approach to tackling poverty in the city for many years through the Dundee Partnership. The publication of the first Fairness Strategy (The Dundee Partnership, 2012) shone a light on the need for the city plan to focus its efforts on addressing the drivers of poverty and reducing inequalities. There was broad recognition that to make Dundee a fairer city, the collaborative approach had to be extended to include citizens whose voices were not being heard. Through the local Fairness Commissions, several recommendations were given which were integral to the development of the DFLP and the implementation of the Fairness Action Plan.

A member of DFLP said:

“Officers and Leaders are really committed through the Fairness Action Plan and making that a sort of distinct charter... you know that distinct recognition of equality, equity and fairness, I think is hugely influential.”

The impact of the Fairness Action Plan goes beyond outlining the strategic aim of the Council. It ensures that the Council and the Partnership are accountable to the citizens of Dundee, not only in achieving the outcomes as detailed in the action plan but also in the process of how to get there. It works on the principle that you cannot expect to achieve fairness without investing time and resources in an equitable decision-making process.

Employees across different areas of the Council explained that commitment to the DFLP is grounded in both the collective urgency for action and an acknowledgement that action must be taken with the people whose lives it will impact.

Andy Smith, Development Officer at Dundee City Council, said:

“Dundee has historic issues with poverty, child poverty, substance misuse and its high profile... everyone’s past trying to come up with theories as to why this is... people are ready to do something cutting edge now that is different.”

Peter Allan, Chief Executive’s Services at Dundee City Council, said:

“This is really important, there wasn’t an independent voice for poverty in the city... there wasn’t an independent group that, you know, could challenge the Partnership and the Council.”

Andrea Calder, Head of Chief Executive’s Services at Dundee City Council, said:

“It’s got to be talk then action... people are committed to taking action and [the Council] are committed to driving that... [DFLP] takes senior people out of their comfort zone, I think it makes you reflect on everything that you hear, the honesty of what you hear.”

There is city-wide recognition that there must be a serious effort made to turn the tide on the high levels of poverty and inequality. This requires an approach that disrupts rather than reinforces existing power imbalances. The Fairness Action Plan has laid a crucial foundation for the anti-poverty agenda in Dundee. It provides a formal agreement between the community and decision-makers that not only prioritises poverty reduction but also puts the voices of people living in poverty at its core. This enables DFFF and the DFLP to formally hold the Council and Partnership to account on progressing the fairness agenda and encourages the Council to view the DFLP as a key component of the strategy.

3. What changed?

Removing barriers to participation

We know that people who live in low-income households are less likely to engage in civic or political contexts and are more likely to be excluded from shaping the political agenda (Catalano, 2022). Multiple structural barriers prevent people from engaging. These can be practical barriers like the cost of travel and childcare, or they may arise from a lack of trust and confidence in politicians who it is felt do not do anything for them. At the same time, low-income households are politically considered a hard-to-reach, or arguably an easy-to-ignore, group (Lightbody, 2017). Yet, if our political systems and public services were more compassionate and responsive to people’s needs, these groups of people would be much easier to engage.

Ethel Davidson, member of DFFF, said:

“People will think they want nothing to do with the Council because [they think] they don’t do much for you, but if they are working through us, we go to the Council, and they know it’s a bit better and it’s not such a barrier to them.”

While the members of DFFF have varying life experiences, they are not representative of the city’s population, nor do they try to be. DFFF has, however, widened its influence by establishing strong relationships with community groups, bridging the gap between the public and decision-makers. DFFF speaks to the wider community to understand what the most pressing issues are for citizens. It creates a safe environment for people who may be concerned about civic participation – ensuring those harder-to-reach groups are listened to. Fundamentally, there is a structure in place through the DFLP which moves community engagement beyond a consultation process. The feedback loop between citizens, DFFF and DFLP empowers people who are most likely to be excluded to instead shape the political agenda and highlight the need for collective action.

Clear and inclusive communications

DFFF has had an ongoing influence on the Council’s public communications. The group has worked with the Council to change its method and style of communication to better engage the people it is aiming to support.

Ethel Davidson, member of DFFF, said:

“We’ve been asked to do a few documents, to see how they are worded if they are going out to the public and things. We will be asked to see them and if we don’t understand them, they change it.”

Andrea Calder, Head of Chief Executive’s Services at Dundee City Council, said:

“We had some interaction with DFFF during Covid... we were looking at inclusive communications getting their sense of what would be better, what we could do more of to make sure people were aware of all the supports that were out there. And then that kind of morphed into the cost of living [crisis]... so we did some more work around cost of living... [asking] DFFF because they knew of what was going on in their communities, and what was most needed... that’s generated us using some of the bus stop billboards to put out messages. That helped us with some of our radio ads that we did and some of the leaflet drops... targeting people who would be, I suppose, hardest to reach... we changed the tone and the language we used across some of the leaflets.”

The Covid-19 pandemic, followed quickly by a cost-of-living crisis, brought into sharp focus the need for targeted communications that increased public awareness of available support. This created an opportunity for the Council to seek advice from DFFF on how its communications and campaigns could be more inclusive and, therefore, effective in reaching those who most needed support. Advice from DFFF led to changes in the Council’s communications strategy, and the Council noted positive feedback from the community.

Andrea Calder, Head of Chief Executive’s Services at Dundee City Council, said:

“We got a lot of really good feedback from the general public, particularly about our cost-of-living information because people were saying you couldn’t walk past a bus shelter without seeing that there was information. People were saying they knew there was help out there if they really needed it, whereas I think probably go back three or four years ago, that wouldn’t have been.”

DFFF has shaped the Council’s inclusive communication strategy during a time of heightened insecurity and hardship. The changes led to increased awareness among targeted groups, ultimately ensuring vulnerable households were receiving the support they were entitled to. As a result of the success, DFFF is a frequent sounding board for various public communications from the Council and other public services in Dundee.

Influencing anti-poverty policy: Fuel Well Dundee

Fuel Well Dundee, which has now had 3 phases and supported over 10,000 households with their energy costs, is one of the initiatives DFFF worked with the Council to design. This came about in response to the finding from a DFFF report (Dundee Fairness Commission, 2020), which highlighted that many people were experiencing fuel poverty because they were at home for an extended period during the pandemic in 2020. DFFF worked collaboratively with the Council’s advice services through the Dundee Energy Efficiency Advice Project in partnership with Scarf to co-design a scheme to support low-income households with their energy costs, provide energy and debt advice and support people with benefit maximisation and accessing employability services. A member of staff from the advice services team explained how they worked with DFFF to design the initiative:

Craig Mason, Senior Manager of Council Advice Services at Dundee City Council, said:

“I wanted to speak to DFFF who commissioned [the report] and get their input into the form so that we could co-produce it... [they were] challenging us on certain things [saying] ‘what about students? You’ve not considered students.’... They also said as a group, they said £30 is not enough.”

The group provided insight and challenged the Council by inserting the voices of people who had experienced fuel poverty into the conversation and pushing them to think about areas they had initially overlooked. One member of DFFF was able to share his experience of being a student and struggling to get the financial support he needed, as often students were excluded from local anti-poverty initiatives.

Eddie Baines, member of DFFF, said:

“I found that most students [in Dundee] were really struggling with poverty, and they were ignored largely because... when the city is developing anti-poverty plans, students are not included because universities are supposed to have that care in place, but students are part of communities. I gave my story as a student, showing what you had to go through... at one point, I took in all the documents I had just to apply for a hardship loan that year... when the letters hit the floor, it was like a phonebook had hit the floor... a lot of the programmes we developed later on included students so I think it made a difference.”

Seeing the immense bureaucracy people go through to access support and hearing how stressful it is to navigate complex systems whilst experiencing hardship has led the Council to take action to improve how it targets resources and minimises the complexity of application processes.

Craig Mason, Senior Manager of Council Advice Services at Dundee City Council, said:

“We changed the form, and we changed the criteria... we upped the value, and we just said right, we’re going to open it up to anyone who wants to apply.”

As the scheme went into its second and third phases, to simplify the process further, people were not asked to reapply. Instead, some basic checks were done to ensure nothing had changed. Some groups who had lower levels of take-up in the first phase were targeted, for example pensioners who had a council tax reduction received the payment directly. Both DFFF and the Council have reflected on the experiences of working together on designing the Fuel Well Dundee scheme.

Craig Mason, Senior Manager of Council Advice Services at Dundee City Council, said:

“Other councils were coming to us and saying how did you do this?… you know, we want to do something similar, and we were able to kind of say, well, we did this, but we also did it with the help of DFFF as well. So, we tried to seed to other local authority areas that they can’t just go ahead and do a scheme and roll it out, you know, it helps if you actually get people with lived experience on board.”

Andrew Lorimer, member of DFFF, said:

“I think that’s been a nice working process with Craig, and he’s come back to us with other things after [Fuel Well Dundee]. Once that relationship is there, they will come back to us for other stuff.”

The Council’s advice services have recognised that the Fuel Well scheme was successful because it involved spending time building relationships with people with lived experience of poverty, gaining insight into what it is like to navigate systems of support. DFFF’s influence stretched through the process from the start, setting the agenda with its report (Dundee Fairness Commission, 2020) that identified fuel poverty as an issue for citizens, to the point of policy implementation and evaluation before the next phase of the scheme. Of course, this was only possible because the right conditions were created whereby the voices of DFFF members were valued, listened to and acted on by the Council.

The participatory process was experienced positively by members of DFFF, not only because their advice resulted in action but also because they established relationships with the Council’s advice services that have led to further collaboration in other policy areas. This highlights the shift that is needed with participation more broadly. Developing structures that support and value participation as a long-term solution to disrupting power imbalances in institutions provides a clear route to designing better policies for communities.

4. What factors supported the success?

An aim of this project was to understand what factors have enabled DFFF and DFLP to work together to influence the anti-poverty agenda and what would be needed for similar models to be replicated elsewhere. Our conversations with the people who have been involved highlighted 2 clear aspects that have undoubtedly shaped their success: the structure of the model, which is shaped by key individuals, and the principles by which it operates.

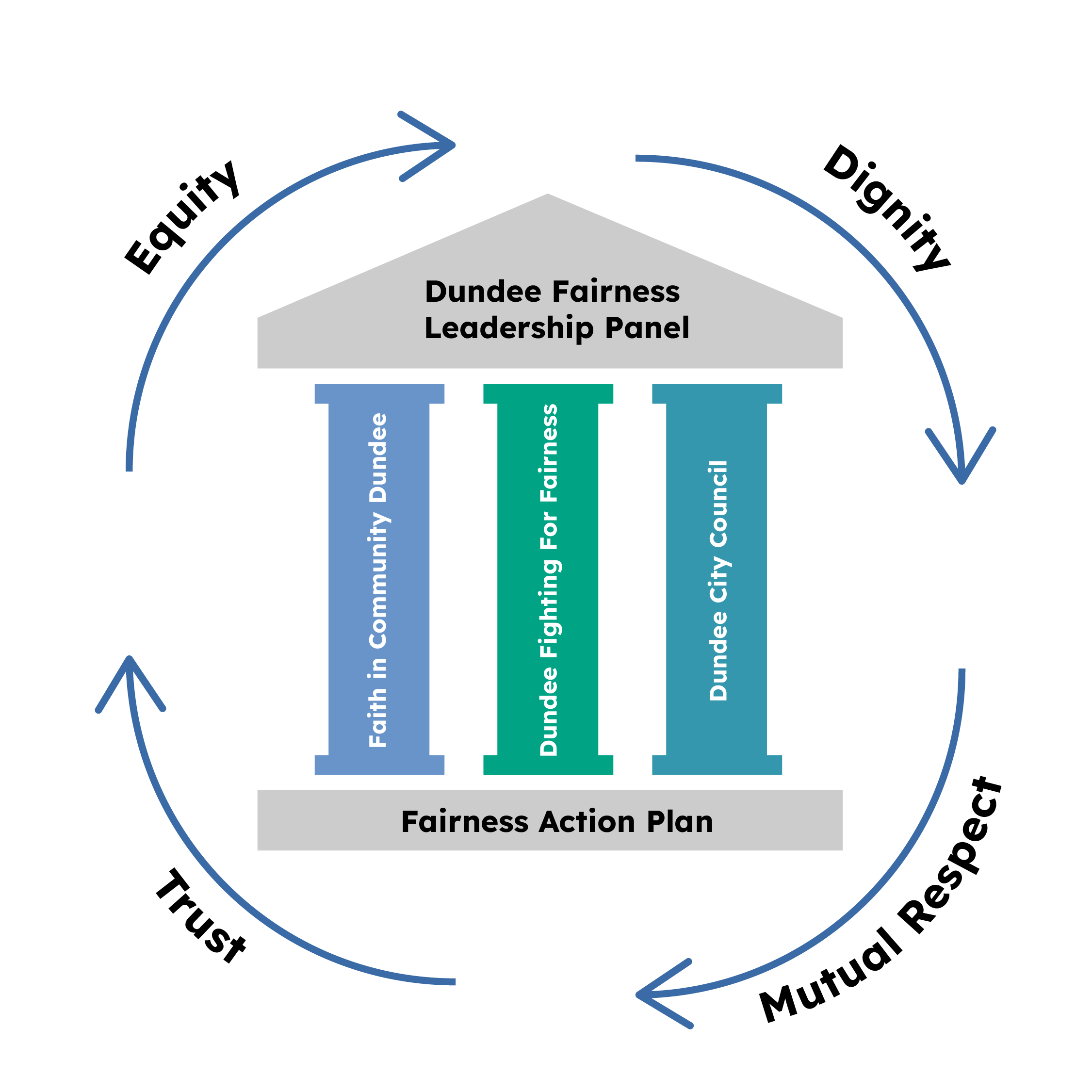

Structure: 3 pillars

As already mentioned, the Fairness Action Plan provides a foundation for the city’s approach to tackling poverty and increasing equality. Additionally, members of DFFF raised the idea that 3 pillars structurally support the DFLP. The people in FiCD, DFFF and Dundee City Council each play a critical role, and although connected in their purpose, the independence of each organisation importantly reinforces their specialised functions.

Many of the people we spoke to stressed the importance of FiCD’s role.

Tony Gibson, Member of DFFF, said:

“People like Faith in Community Dundee, a group like that in the city who are proactively focused on, not necessarily what we talk about or what we discuss but making sure it can happen, that would be a pillar.”

Tammie Brown, member of DFFF, said:

“They are such a big part of this. I don’t think we could run as efficiently as we can if it wasn’t for Faith in the Community [Dundee]. [They] keep us all up to date on everything that’s going on, and the relationship we have with Faith in Community [Dundee] is amazing, we all have a friendship that has budded from the working relationship.”

FiCD provides essential support to members of DFFF and critically mitigates the risk that comes with involving people with lived experience in policy-making. People who use their voice and experience of difficult personal circumstances to engage in systems to influence change can be either directly or indirectly prompted to re-visit traumatic experiences, while also navigating ongoing personal stresses. Far too often, people with lived experience are consulted on matters with very little support, follow-up or resulting action. While there has been a shift towards giving more consideration to the structures that need to be in place, there is still a long way to go to get this support right for people.

FiCD plays a critical role in ensuring that members of DFFF are not re-traumatised for the purposes of designing better policies. They have spent time, over several years, building relationships with each individual, skilfully providing wraparound support for those involved. The outcomes of engagement and empowerment that DFFF members have experienced are a result of FiCD’s investment and skill.

Additionally, FiCD brings an extra layer of external accountability, creating a more neutral space for DFFF to discuss issues before engaging with decision-makers.

Jacky Close, Director of Faith in Community Dundee, said:

“[the Council] recognise if you hold it in-house you can’t hold yourselves to account, if you sit slightly separate, slightly overlapping, where it’s definitely very much a council thing but also not, so we hold that element of independence.”

Accountability must come with a willingness to accept responsibility for actions taken and an understanding that the judgement must come from an external voice. While DFFF is the voice that holds the Council and Partnership to account, it is equally important that DFFF members are supported in a space that is separate and safe.

Andy Smith, Development Officer at Dundee City Council, said:

“It’s quite important that the group has its own space and its own communication channels that are safe… because even though we try our best, you know, at the Council … people will still feel like, ‘well, I don’t want to ask that question’.”

Chris McDonald, Member of DFFF, said:

“There’s a lot of honesty in the group, but everything does get kept confidential.”

Of course, DFFF is the central pillar, bridging the gap that exists between citizens and political systems, and amplifying the voices of people who have lived experience of poverty and inequality. For DFFF, an independent but connected space is vital to ensure feelings of safety and security for the people involved, the importance of which should not be underplayed in this context. Many members of DFFF said that their involvement in the DFLP had increased their confidence because they felt listened to. One member of DFFF gave an example of a time she felt empowered by the response she received after raising an issue, first at a DFFF meeting and then at the panel:

“Because we sit on the leadership panel through DFFF, I’ve found that has given me more confidence... my daughter’s got allergies, and we were talking about the use of foodbanks but there’s not any provision for allergies, so I raised that to the panel and then off of that there was then a fund awarded to the larders to buy allergy friendly food, and I felt quite empowered to be able to say this is what I found difficult and I’m not the only one... so being able to first mention it at the DFFF meeting and then bring it up at the panel, it was really empowering, and I felt like I had a voice.”

The final supporting pillar is the involvement of the Council. The Council helps coordinate the involvement of the other public services. It has the power to make decisions and the funding to enable action. Governments, councils and organisations must be willing to see value in the commitment to a model like the DFLP. Otherwise, the impact will be weak.

John Alexander, Former Leader of Dundee City Council, said:

“If you’re a council that’s not willing to say we get things wrong, and we’re not going to get everything right and you need to challenge us, there’s no point first and foremost, because from my perspective, and I would say this as the leader of the Council, the Council is kind of integral to it because it’s the conduit, the link that supports and funds a lot of the stuff, so first of all you need the Council to be fully on board, if you haven’t got the Council fully on board then it’s going to be acrimonious.”

Peter Allan, Chief Executive’s Services at Dundee City Council, said:

“You need a council that’s open to criticism, looking at itself, and is comfortable with hearing an alternative voice.”

A member of DFFF said:

“The Council needs to genuinely want to hear these lived experiences.”

Policy-makers must recognise that they will sometimes make poor decisions. These decisions have a real impact on people’s lives and often affect disadvantaged communities the most. Deeply engrained systemic inequality means that there is a knowledge gap within these institutions. Policy design does not always translate into how people interact with systems. Therefore, meaningfully engaging with those who have experienced the complexity of, for example, applying for hardship funds or accessing debt advice, helps to rectify the gap and leads to better policy design.

These 3 pillars (FiCD, DFFF and Dundee City Council) have equally supported the development of DFLP, which brings all actors together under one umbrella to lead the fairness agenda in Dundee. Removing any one of these pillars from the structure puts the success and integrity of the model at risk.

Ultimately, an approach like this requires financial investment, commitment from key players who can make change happen, skilled individuals who provide trauma-informed support to people who share the lived experiences and partnerships across a well-connected third sector and public sector.

It is important to underline the role of key individuals in the DFLP’s success. It has undoubtedly relied on their belief, skills and drive to shift thinking and practice in Dundee. The core requirements of those individuals are: a commitment that change is possible, a belief that they have a role to play in that change and the ability to listen and an instinct for collaboration. It also necessary for those who hold power to acknowledge that power and be open to sharing it.

As Tony Gibson, member of DFFF, said:

“One of the smartest things we did was to emphasise that this is not a council thing, this is us, Dundee citizens.”

This approach is about believing and leading with the idea that this is about improving people’s lives and the communities we all live in. It is about shattering notions of ‘us’ and ‘them’ and re-building a shared mission that provides better outcomes for everyone involved.

Principles

A number of principles have guided the development of DFFF and the DFLP. These principles can be learnt from as a way to establish similar lived experience models in other places.

Focusing on the system

One of the tensions with embedding lived experiences in policy-making is that experiential evidence is deeply personal, while the issues it aims to influence are structural. Those who share difficult personal experiences in public circles can be left feeling used, particularly when no tangible action results. At the same time, policy-makers struggle to justify policy change without clear data-driven insight into structural issues like poverty. DFFF and the DFLP have managed to carefully navigate both of these tensions by focusing on the system.

Jacky Close, Director of Faith in Community Dundee, said:

“I remember [the Council] saying we are not going to make a change on one person’s experience... and that’s when we shifted the commissions and panel to ‘we’re hearing these experiences from people, well let’s go out and ask questions specifically more around that’… and then you start to build collective experience… rather than drilling into one person’s experience which is very hard… so yeah, it’s the system, it’s not all about one person’s story.”

A member of DFLP said:

“Somebody can bring a really helpful individual perspective. But is that representative of the wider population, you know? So I think we have more confidence because of the approach with a fairness leadership panel where they will go out there and they’ll talk to people and they’ll take questions and you know they’ll read up and all that sort of stuff. So… you can be confident that there’s a kind of wider representation through those individuals around the table.”

In the former commission model, there was a greater focus on storytelling as a means of learning from people’s experiences. However, this approach shifted as the commission developed into DFFF and the DFLP as it became clear that action was much more likely if systems-level issues could be evidenced beyond the experiences of a few individuals. This is not to say that the experiences of individuals are not considered part of this, but that extra steps are taken by those individuals to gather a wider evidence base.

Daisy Field, member of DFFF, said:

“We don’t really talk about our personal experiences, like our stories, so much. We might choose when to bring up personal experiences... I think [in DFLP] we’ve found a really nice sweet spot, where any individual micro level experience is valid and considered and... then widening it out to a systems level.”

A systems-focused approach succeeds in 2 ways. First, and importantly, it balances giving people the space to discuss their lived experiences whilst prioritising their dignity. Second, it strengthens the integrity of the evidence and therefore pushes decision-makers to make change.

An equitable and dignified approach

It is crucial to take the time to invest in the relationship-building element of a participatory model like this. It was decided that everyone involved in the DFLP should be introduced to one another on a person-to-person basis. This strategy guarded against any pre-conceived ideas about job titles or people’s backgrounds interfering with building relationships.

Tony Gibson, member of DFFF, said:

“Nobody knew what anybody’s position was at the very beginning for the first few meetings, we weren’t to talk about it so you had to engage with people on a social level.”

John Alexander, Former Leader of Dundee City Council, said:

“The first few meetings that we had we didn’t discuss any of the agenda, it was really about getting to know each other, feeling comfortable with each other and almost just humanising the whole process rather than seeing it as a process.”

Taking an equitable approach is about levelling the playing field and breaking down the barriers that inevitably exist between groups of people who are systemically separated by our society’s design. It creates space for the group to connect as people with a shared purpose. By equity, we mean treating everyone with fairness and dignity while recognising that people have unequal experiences and privileges and therefore should be provided with the varying support they need to participate. This re-emphasises the need for the right support systems to be built into the structure of the model.

Engendering mutual respect and trust

Another important part of relationship-building is the acquisition of mutual respect and trust. One risk in a process like this is that you get 2 very different groups in the same room and the conversation moves into the mode of attack and defence. Therefore, it is essential to lay down a foundation that creates the conditions whereby all parties are willing to listen and learn from perspectives they may not have previously considered.

Tony Gibson, member of DFFF, said:

“Proactively promoting mutual respect… is essential to the free flow between people that live in different bubbles, for one, but also have different ideas.”

Peter Allan, Chief Executive’s Services at Dundee City Council, said:

“We’ve put a lot of effort into making sure that everybody knows that this isn’t just a council-bashing exercise and… this isn’t a Council defending exercise either. [We say] listen to people and try and learn more… because your experience of these things as the chief executive or as a head of service may not be the full picture.”

Andy Smith, Development Officer at Dundee City Council, said:

“People can be nervous about being involved in case they become personally culpable… but that’s another part about capacity… I’m given the time and space that I need to carry out actions and to follow things through that result from meetings with the Fairness Leadership Panel, but that that accountability is massive and I think that’s where the nervousness comes from.”

Eddie Baines, member of DFFF, said:

“I don’t think it would have happened if the Council wasn’t fully invested in it... and the fact that they are willing to sit down and hear that they are wrong and not take it offensively.”

It is about underlining the importance of listening to and respecting alternative voices and ensuring members of staff have the capacity to properly engage and respond. For DFFF members, having open conversations with the decision-makers about some of the constraints they face, whether that be budgetary, legal and so on, can help to focus efforts on areas the group has greater influence over. Mutual respect should be embedded to support positive communication and understanding right from the beginning of a process like this. However, trust is built over time.

Craig Mason, Senior Manager of Council Advice Services at Dundee City Council, said:

“They started to trust us because we were coming back to them with, you know, tangible changes to… what we could do, we changed to take into account their feedback. [Now] you go into those meetings and it’s not as if we have to kind of you know, engender that trust again with them. You know we’ve got that experience from before and we know that we can work with them.”

Tammie Brown, member of DFFF, said:

“If there is no trust there’s no relationship… to actually have the Council listening and then not just listening but actually taking action with us… is amazing.”

Terrie Bustard, member of DFFF, said:

“There’s loads of different people who have different backgrounds… and we respect each other.”

Trust starts to build not only because people feel listened to but also because they can see that their participation has resulted in real changes that will positively affect the community. Establishing trust over time has helped solidify the relationship and encourages a sustainable and long-term approach to participation. John Alexander, the now former leader of the Council, said that the DFLP is ‘part and parcel of the approach that the city takes towards the issues of poverty and deprivation’.

Both the structure and the principles of this approach can and should be learned from as a blueprint for meaningful lived experience participation in anti-poverty policy design.

5. Conclusion

The evidence from this research shows that, with genuine investment, a collaborative approach to tackling poverty:

- strengthens the relationship between the community and decision-makers

- changes perceptions between groups of people that are systematically separated

- supports people who often go unheard to instead shape the political agenda

- provides a clear route to designing better policies for communities.

The DFLP starts with the shared belief that this is about a commitment to improving people’s lives and the community everyone lives in. The way to achieve this is to work in partnership, across councils and public services, to put the voices of people who have lived experience of poverty and inequality at the centre of efforts to tackle these issues. This requires involving people who value and believe in this approach. Yet, it remains necessary to establish a structure and principles that can support its function, integrity and sustainability. We must learn from the successes of local initiatives and shift the balance of who makes decisions around poverty and inequality more widely across Scotland. As one member of DFFF said:

“Councils need to do this sort of work because it makes the public more on board, we are all wanting the same thing ... you are there to make things better for your city or town and the only way you can make things better is by listening to people who have the most difficult experiences to understand and try and make it better.”

You can read more about the successes of Dundee Fighting for Fairness and learn more about the Dundee Fairness Leadership Panel.

References

Catalano, A. (2022) Inequalities in voting and volunteering: who participates in Scotland?

Dundee Fairness Commission (2020) Investigating the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdown

Lightbody, R. (2017) ‘Hard to reach’ or ‘easy to ignore’? Promoting equality in community engagement

McKendrick, J.H. Marchbank, J. and Sinclair, S. (2021) Co-production involving ‘experts with lived experience of poverty’ in policy and service development in Scotland: a rapid review of academic literature

Scottish Government (2015) Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act

The Dundee Partnership (2012) Fairness Strategy

Dedication

This briefing is dedicated to Tony Gibson, who passed away unexpectedly in May 2024 while the research for this briefing was being carried out.

Tony was a founding member of DFFF and played a crucial role in supporting the other members during the Covid-19 pandemic. He was also one of the co-chairs of the DFLP. He fundamentally believed in the ability to create change and justice by bringing marginalised people’s voices closer to those in power. He also loved Dundee and wanted to improve the lives of his fellow Dundonians. As he said of himself and his DFFF peers:

“None of us are natural politicians, but all of us are Dundonians, and we want the best for our city, and I think as far as good people are concerned, we have an overabundance of them.”

This briefing is part of the power and participation topic.

Find out more about our work in this area.