Is the ‘will of the people’ changing?

Personal reflections on the impact of voter volatility on styles of campaigning, governing and political communication from JRF's Director of Communications and Public Engagement, writing a few weeks before the July 2024 General Election was called.

Is the obsession with political attitudes new?

In a recent Times column, the avowed anti-populist Matthew Parris criticised the concept of ‘the will of the people’ (paywall). ‘The people’, Parris argued, are not a real thing. Rather, ‘there exist many persons with many opinions, held with varying degrees of certainty and fluctuating levels of intensity, and among whom at any given moment a majority may sometimes and often temporarily be found for a stated proposition or choice.’

Parris is by no means the only sceptic about what can be meaningfully read from the results of referendums and, by extension, I assume, modern polling. In their 2016 book Democracy for Realists, US political scientists Christopher Achen and Larry Bartels draw on 7 decades of scholarly literature to make a strong case for just how little attention most voters pay to politics outside the election cycle. And for how much voting at the ballot box and preferences reported to pollsters are done for expressive, contradictory and often irrational reasons.

Their conclusion that politicians should heed the public’s voice while relying on input from people with specialist knowledge and experience is hardly controversial. Indeed, Achen and Bartels’s observation that voters’ more lightly held attitudes will often change in line with the candidates they believe to be on their side implies that successful politicians hold the power to bend political reality around certain ideas, if only temporarily. In other words, to lead.

Yet one of the most striking developments during my career since starting to follow politics professionally 18 years ago is the growing visibility of public opinion research in debates about policy. Whereas in the early 2000s polling experts would start to appear on screens a few months before an election, then become forgotten shortly afterwards, they are now more consistently present in news media.

The shift is reflected in private forums. Pitching ideas for reform between 2006 and 2010, I don’t remember discussions, even with Cabinet members, dwelling on public opinion in any great depth. This was not because we or they thought it irrelevant. Nearly all Westminster politicians pride themselves on trying to stay in touch with what their constituents are thinking, through their post bags, surgeries and doorstep meetings.

It was just assumed that national voter strategy and the nuances of political communication were dark arts and largely the domain of the small teams surrounding the respective party leaderships. Certainly, the non-profits I worked for at the time lacked the budgets to commission research that has since become commonplace.

Now, it is hard to imagine not arming sympathetic MPs with data to help them persuade colleagues about the potential popularity of a specific idea or cause or at least evidence that its adoption won’t cost them too much support, alongside the substantive case. And it is striking how much, after 2019, conversations with MPs in every party would eventually touch on how the topic at hand related to the views of ‘Red Wall’ voters.

If Parris, Achens and Bartels are right to question just how much stable moods and preferences can be truly discerned from polling, then this cultural shift is a cause for reflection.

What is causing the preoccupation with public attitudes?

Looking back, I suspect at least 3 connected developments are behind it.

First, on both sides of the Atlantic, the shock that half the UK felt at the vote for Brexit (and some then about Donald Trump’s presidency) provoked a huge amount of soul searching among metropolitan elites in the media, politics, and civil society. In retrospect, troubling economic data and the growing popularity of anti-establishment parties were just the early signs of rising disenchantment with the political economy that prevailed during the 1990s and early 2000s. The surprise results delivered at various elections after 2010, often in quicker succession than we were used to, enlarged the market for information about what voters think and feel.

Second, while income, class and age remain important predictors for how people vote, deep-seated political tribalism is declining and turnout levels have become spikier. Between 2010 and 2017, consistently more than 50% of low-income voters either changed their minds about whether to vote or not or changed which party they supported. The growing importance of educational divides, and the cultural differences they are taken to represent within more marginal parliamentary constituencies, pose new strategic dilemmas for politicians. Labour’s currently enormous polling lead shows that talk of a great realignment in the run up to 2019 was overblown. Instead, the major parties face the task of perpetually stitching together coalitions that are both more diverse and fragile. Every policy proposal is measured for the risks they pose to holding existing and potential coalitions together.

This is even though perception of competence, especially economic competence, is still the overriding determinant of who ends up in power. A purely relative concept, it has the advantage of rooting our politics in reality. It cannot be a coincidence that average real earnings were starting to rise in the years shortly before David Cameron achieved his majority in 2015.

However, when (thirdly) economic performance is flat and local and global forces impose limits on governments’ power to turn things around quickly, the only available option is to try to create an impression of competence elsewhere. Largely by using their bully pulpit to boost the salience of any other issues thought to matter to voters; and where they have a shot at maintaining a competitive advantage.

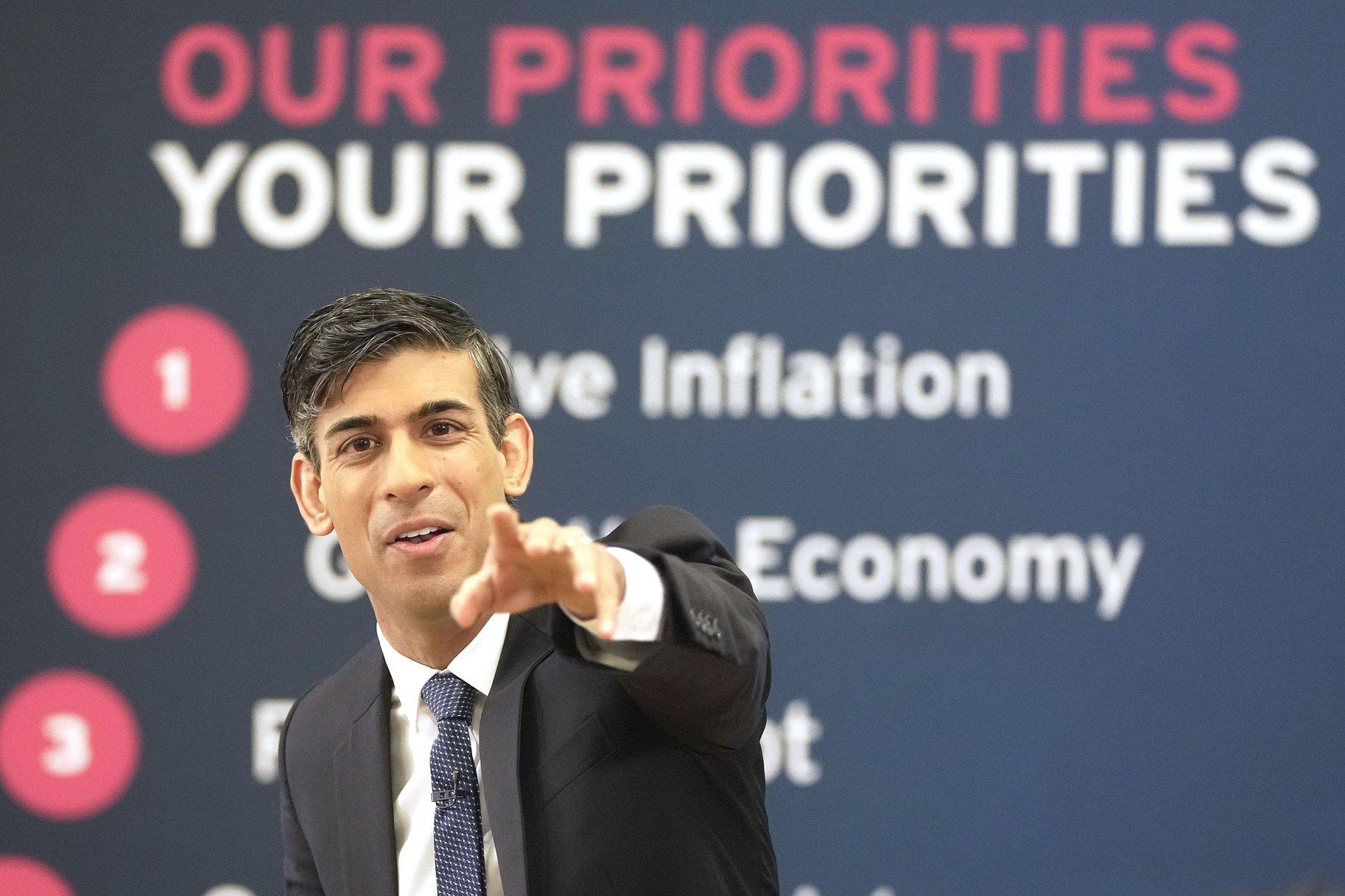

This may help to explain the zigzag quality of the current Government’s policy and communication strategy. Lingering inflation, anger about the effects of the 2022 mini budget, and low productivity have destroyed their lead on the economy. Regular briefings about the PM’s preferred style of ‘quiet delivery’ aim to prime voters to assign him at least some credit if their sense of economic wellbeing improves noticeably before the next election. In the meantime, having lost their lead in virtually all issue areas, ministers keep talking about the issues where they traditionally dominated such as immigration and national security, hoping that memories of past ownership keep loyalists on side.

Is this good for our politics?

Speaking personally these developments are, to say the least, a cause of deep ambivalence. In my own field (of non-political campaigning) Daniel Stanley of the Future Narratives Lab has written powerfully about the need for change advocates to understand ‘context, language, concept, implication, and culture, and use this understanding to build a system of thinking that appeals to common human values, personality, and preferences in our modern cultural context.’

He is right that too often we start with the question of what message will change people’s minds; we should be thinking harder about if our propositions genuinely have some prospect of speaking to the values and aspirations of large enough cross sections of the public. This is exactly where the JRF and Trussell Guarantee Our Essentials campaign began and it is all the more powerful for it.

Anything that forces people who hold power in various arenas to be more curious about what their fellow citizens are experiencing in their lives, what consideration they think we owe to each other, and who they believe comprises that ‘we’, is hard to quibble with. Inasmuch as public attitudes research provides a way for voters’ moral calculations to be considered alongside technical policy questions about cause and effect, then lively interest in it is probably a good thing.

But there are downsides. This type of research is expensive, especially those studies that try to grapple with and predict the enormously complex relationships between voters’ attitudes towards individual issues, their entanglement with social identities, and how they are weighted in the judgments made about parties’ competence, and the character of political leaders. But even simpler snapshots must be taken regularly to account for shifting ground.

The more they come to be seen as an indispensable tool for evaluating the merits of individual policies, the more it potentially advantages well-resourced interest groups who can afford analysis at the levels sufficient to satisfy political strategists in the major parties. All of whom are desperately trying to spot actionable trends.

It is therefore important that organisations like More in Common, the Fairness Foundation, British Future and UK in a Changing Europe continue to democratise access to strategic insight. As a funder, JRF has also tried to resource the undertaking of publicly available attitudinal research relevant to our traditional and newer areas of concern. This ranges from exploring the aspirations of low-income voters specifically, to tracking the swells in the wider climate of public opinion that may regulate our and allies’ ability to secure meaningful change.

At other times, we have focused on specific topics, such as our recent funding of Labour Together’s innovative research on the meanings that voters being targeted by the Conservatives and Labour ascribe to economic security, and a more forward looking exercise with the LSE’s International Inequalities Institute on the dominant framings around wealth inequality.

Struggling to make a real-world difference

My biggest worry about this trend concerns the practice of politics itself, however. Britain is in serious trouble. A politics that aims to improve people’s lives is just harder to conduct than past eras. We are a decade-and-a-half into a period of stagnation, with the living standards of low- and middle-income households now further depressed by the cost of living crisis.

The list of challenges is daunting: deepening poverty and destitution among the worst-off households, under-investment, sclerotic rates of housebuilding, high levels of spatial inequality and a slow burning emergency in social care to name just a few. None of which have simple solutions.

In a world lacking silver bullets, where states must balance numerous competing vested interests, and are subject to gilt markets willing to punish any signs of fiscal ill-discipline, it has become progressively harder for voters to connect specific actions taken by a government to their sense of wellbeing or lack thereof. The oft reported disillusionment with politicians and fatalism about politics more generally is much more about this than frustration with the sleazy antics of a few individuals.

The speechwriter Philip Collins described a healthy democracy as requiring ‘a dialogue between leaders and led in which both are understood.’ Yet so much of political rhetoric since 2016 has seemed designed purely to reassure subsets of voters that they are being heard even as ensuing actions fail to make an appreciable real-world difference. Rishi Sunak, when first competing for the Conservative leadership, seemed initially tempted to take a different tack, moving away from the ‘cakeism’ of his predecessor. He promptly lost to Liz Truss. Given the reports from focus groups that voters are yearning for clarity and direction it is possible that had he been making his arguments to a larger electorate than the Conservative membership he might have been rewarded. The Labour leadership also appear to be trying to revive the lost art of managing voters’ expectations, which is welcome.

But they are not immune to the structural pressure to reflect the public mood. If the challenge of politics today is to hold together fragile coalitions while trying to deliver within straitened circumstances, what might the flows of voters over the past year tell us about what to expect in the next parliament?

What might policy look like after the next election?

Assuming that the polls are right, Britain is heading for a Labour-led government. The growing efficiency of their vote - as evidenced in recent local elections - implies that they are rebuilding support among an amorphous middle of Red Wall voters for whom the economy is the primary concern, while attracting more suburban voters in the South.

The main unknown is how neurotic Labour chooses to be about the nature of any eventual majority. Many on the party’s left will urge the leadership to treat a large winning margin, and the likely disarray among the Conservatives, as a mandate and opportunity to make sweeping changes.

Those who favour caution will point to the fact that Sir Keir Starmer has failed (at least at the time of writing) to match David Cameron’s favourability ratings in 2009-2010 or Tony Blair’s in 1996-1997. All of which, they might argue, implies that Labour in office should not take their newfound reputation for competence, won largely because of Conservative failures, for granted.

But this still leaves open the question of what their voting block might expect competence to look like from a Labour-led administration? Both in terms of continuity and change from the current government.

All predictions are hostages to fortune but 3 important trends provide some clues. First is research by Yonder Consulting, funded by JRF with Labour Together which reconfirmed how central the cost of living crisis is to people’s sense of their own security. In the short-term this provides fiscal hawks with the political cover to resist internal demands for anything with inflationary risks or the potential to prolong the period of higher borrowing costs for households.

The second is that the sheer breadth of Labour’s emerging coalition will make them less reliant on retired voters compared to recent Conservative governments. The Economist’s model of individual voting behaviour predicts that despite the country having aged since 1997, Labour’s median voter will be 2 years younger than they were nearly 30 years ago. Economic and social policy is likely to be more attentive to working-age households than over the past 14 years.

The third and most interesting trend relates to the fracturing of the Brexit-leaning vote that cohered behind the Conservatives in 2019. So far, 44% of 2017 Labour voters that opted for the Tories in 2019 report that they now intend to vote for Labour, while 18% signal support for Reform. If we assume that the Brexit voting 2017 Labour voters now returning to the fold are on average more focussed on the economy than those now voting for Reform, this potentially provides a Labour government with more room than the Conservatives felt they had to pursue stronger economic links with the European Union.

Conclusion

Unlike the situation in 1997, when the state of public services seemed to be voters’ dominant concern, polls suggest that enough of the electorate is resolved to task an incoming Labour administration with easing the financial squeeze that many families now feel.

Few of the measures needed to make the country more attractive to investment or more productive will yield immediate benefits. A different style of messaging will therefore be necessary, one that communicates to voters the need for patience and for tough choices while vividly articulating how the steps being taken will make a positive difference.

Unlike the Conservatives after 2019 who seemed unsure about how to do this with their newly diverse block of voters, Labour has the advantage that the fissures within their emerging coalition are less pronounced.

The question is will those voters, experts in their own lives and used to feeling let down by politicians, extend them much beyond the briefest benefit of the doubt.

This comment is part of the public attitudes topic.

Find out more about our work in this area.