The future of care needs: a whole systems approach

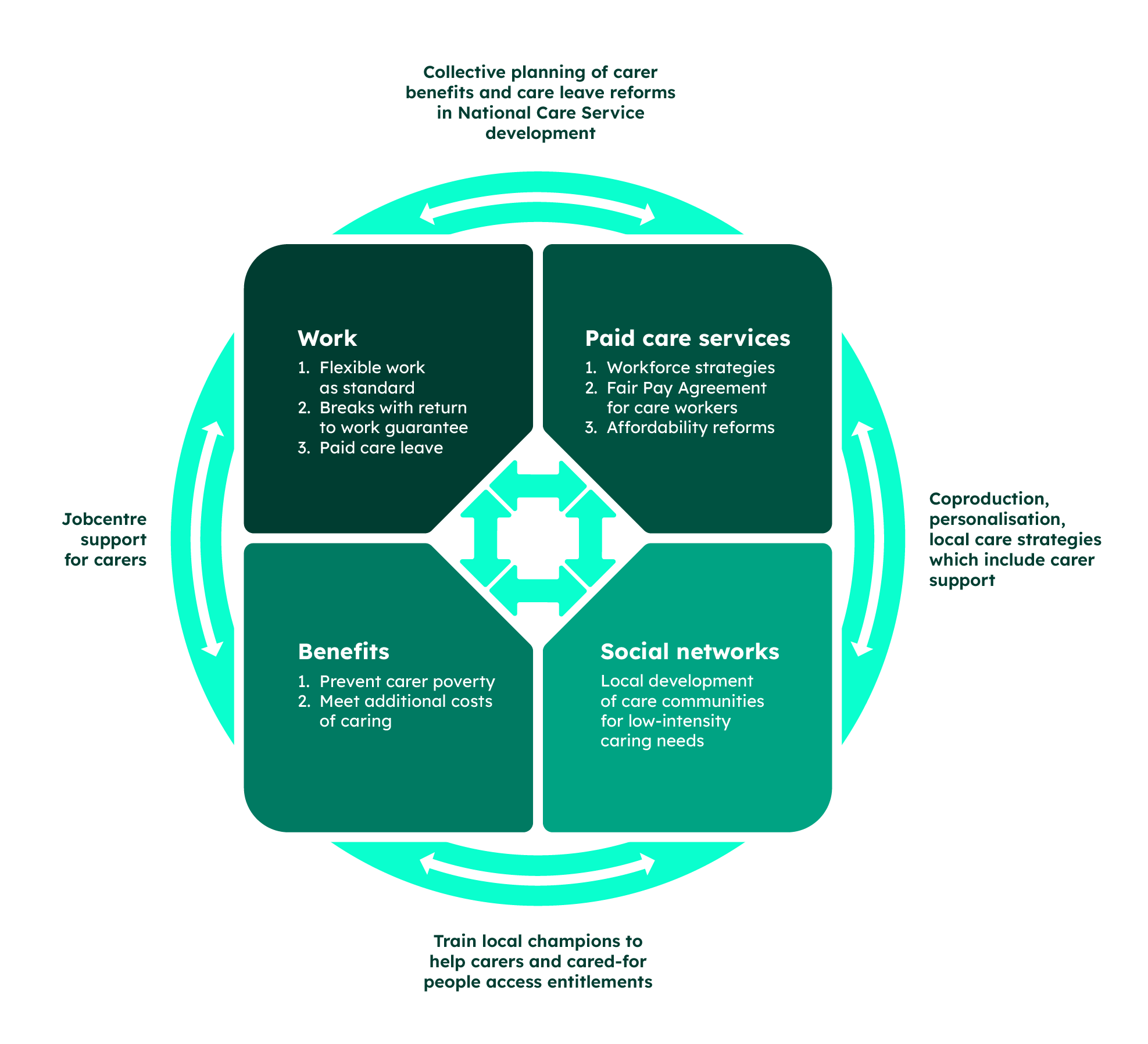

This new approach brings together action to improve paid care with support for unpaid carers and social networks.

1. Introduction

The country’s health is changing. We are living longer and more of us will need care in the future.

This will lead to an increase in the need for paid care services but will also require an increase in informal care because not all people who need care receive paid care, and some of those who do receive both formal and informal care. Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) analysis found that over the period 2016–2022, over half of people aged 65 and over who were being cared for only accessed informal care, around a quarter accessed both formal and informal care and just under a fifth only accessed formal care.

Informal care is an inevitable part of how care needs are and will be met. Some of this is due to unmet need for paid care services or high costs but much is due to people choosing to care. JRF research found that, for people providing the majority of care for someone, 46% of unpaid carers and 40% of parents say their main reason is that they want to.

There are genuine benefits for cared-for people of drawing on informal care as some needs fall outside the routine of formal care services while carers can also help people access the right paid care services.

If the number of carers rise only in line with population growth, JRF analysis projects that by 2035 there will be an extra 400,000 people in the UK caring for the elderly, sick and disabled for 10 or more hours per week, an 11.3% increase compared to now. Of these new carers, 130,000 will be of working age.

If we include those caring for fewer than 10 hours per week, this figure rises to 990,000 additional carers, a 10.6% increase compared to now. It is likely that unmet care needs would also continue to rise alongside this, given that the proportion of over 65s in the population is growing faster than the average.

We also found that rates of care intensity are changing, rates of very high-intensity care (35 hours+ per week) are higher in the UK now than 10 years ago, driven by more prevalent chronic and degenerative conditions and more people caring for working-age disabled people who need long-term care.

These changes point to a future where care needs are longer, more intensive and more complex. Focusing on expanding the availability and affordability of paid care services is important to meet growing and specialised needs – but this alone will not be enough.

In order to fit the right blend of informal and formal care to people’s individual needs the state needs to enable real choice in the system. This means taking action in 4 key areas:

- Paid care services need to be more available and affordable, particularly for those on low incomes and with few savings.

- Work should allow people to care, through flexible working or paid care leave.

- The benefits system for carers and parents should provide carers with the resources and dignity to do the job well.

- Social networks should be strengthened locally so people can more readily give and access ad hoc support in their community.

Supporting and incentivising unpaid care is especially important to support more people to be carers as changing gender and work norms mean that, rightly, we are moving away from the expectation that women are expected to be caregivers more so than men.

As people draw on multiple sources of care, policy-makers need to co-design and embed systems in one another. This means:

- seeing the availability and financial security of informal carers as a central plank of the National Care Service, and factoring in the role of local social networks in providing ad hoc physical and emotional support to personalise care

- Jobcentres giving support to carers who want to work, even for a few hours a week, and ensuring carer benefits do not penalise work

- supporting local carer organisations who can help carers access the benefits they are entitled to.

There is a structural obstacle to this kind of working in government currently where future care needs are planned for primarily by the Department for Health and Social Care focusing on the paid adult social care system, with financial support for unpaid carers primarily designed and delivered by other departments separately and with respect to a set of different departmental agendas.

The first step government should take to solve this and set into motion a new strategy for meeting these needs is to create a Future Care Needs Taskforce. This would be chaired by the Department for Health and Social Care with representatives from the Department for Work and Pensions, Department for Business and Trade, the Ministry of Housing, Local Government and Communities and the Department for Education. The taskforce would plan not only how to expand paid care services but also how to unlock the caring capacity of family and social networks through paid leave, more generous carer benefits and community support.

2. Rising tide of care needs

Globally we face a ‘crisis of care’ as ageing and changing demographics drive increasing care needs which governments are struggling to meet. These care needs can be met through a range of different services and support, such as paid, subsidised or free care services in a formal setting or in one’s own home. It could also include paid help like cleaners and handymen and informal support from family, friends and social networks. Not meeting these needs can have serious consequences — it can directly affect health and development for the cared-for person, and can also put pressure on adjacent sectors like health and the labour market.

In the UK we face this challenge too. Our population is getting older (Office for National Statistics, 2022) which means our health and care services are looking after people for longer than initially anticipated. We’re also seeing more working-age adults seeking formal care services, particularly adults with learning difficulties who need very long-term care (Hu et al., 2020).

An ageing population does not automatically mean a huge increase in the need for care. Research has found that older people are on average managing their conditions through the NHS (Raymond et al., 2021) without needing more formal care and recent generations seem to be healthier as they age (Kingston et al., 2022). Beyond adult social care, birth rates have been low in the last decade meaning there will be fewer young people to care for older people in the long term – but in the short term this can lead to a lower demand for childcare and primary school closures in some areas (Hackney.gov.uk, 2023).

The scale of change, however, points to the scale of the challenge. The Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) estimates that the number of disabled older people unable to perform at least one instrumental activity of daily living without help will increase by 69% between 2015 and 2040, from 1.7 million in 2015 to 3.0 million in 2040 (Wittenberg et al., 2018). They also estimate that the number of adults with learning disabilities, mental health problems and physical disabilities will increase (Wittenberg et al., 2018). The Care Policy and Evaluation Centre estimates, based on population trends, that 29% more working-age adults, and 57% more over-65s, will need care in 2038 compared with 2018 (National Audit Office, 2021).

The Health Foundation has estimated that the prevalence of conditions with high healthcare needs, such as dementia, heart failure and diabetes, will increase significantly by 2040. These are largely managed in primary care, driving up the demand for support from GPs and community health settings (Watt et al., 2023).

More people will need care in the future

Changes in the health of the nation will change the volume and type of care needs, and in turn, the demand for care.

PSSRU estimates that paid home care, residential care and physical support services in England will all face significant growing demand by 2040: numbers needing publicly funded home care are projected to increase by 87% compared with 2015, while residential learning disability care service demand could increase by 72.5% over the same period. Based on the projected growth of the over-65s population alone, Skills for Care estimate that the adult social care system in England will need 440,000 more paid care workers by 2035, a growth of 25% from current numbers (Fenton et al., 2023). Unsurprisingly this will incur a significant cost, with researchers estimating the total cost of paid care services could more than double by 2040 if needs were met (Wittenberg et al., 2018).

But paid care services are only one part of meeting care needs. There are an estimated 3.6 million unpaid carers in the UK providing care for more than 10 hours a week, this rises to 9.3 million if you include carers undertaking fewer hours of care a week. There are 7.2 million parents with dependent children in their household undertaking at least some unpaid care. This fundamental domain of caring meets the vast majority of care needs but receives much less attention in policy debates. These unpaid carers are usually women who have to leave the labour market to care and face a financial ‘caring penalty’ (Jitendra et al., 2023).

Looking at data on people’s interaction with care services, we find that in elder care, informal care use far outstrips formal care use, while for childcare a significant minority do not use any formal childcare. JRF analysis found that over the period 2016–2022, over half of people aged 65 and over who were being cared for only accessed informal care while under a fifth only accessed formal care. For children, the numbers accessing formal care were higher. Just over half of families of children in England aged 14 and under used formal, paid services over the same time period. The variance in formal care use between these two groups could be for a range of reasons: for example, childcare is comparatively more affordable and accessible than adult social care.

These are likely conservative estimates as people can draw on multiple types of care to meet their needs. Our analysis found that around a quarter of people aged 65 and over being cared for accessed both formal and informal care. We also know that children being cared for formally, especially very young children who need round-the-clock care, are also being cared for informally by family or other networks.

Finally, we also know that paid support which we might not class as ‘care’, like neighbours checking in and cleaners and handymen helping people live independently, is an important component of meeting care needs, but which is often forgotten. Our analysis shows that approximately 70% of disabled people over 65 using care in the UK received help through paid support services like these.

Unpaid care is a crucial part of the future of care needs

Expanding paid care services will help reduce the burden of care on women and those who have no other choice to care, and are a crucial way to help women enter and stay in the labour market. But it would be very difficult for government to eliminate unpaid care altogether.

People become unpaid carers for a range of reasons, and many genuinely want to care, while others feel they have to or have no other choice but to care (for example, because their household cannot afford paid care). Forthcoming JRF research on people’s attitudes towards care shows how people, despite barriers, do want to care. When asked to score how happy or unhappy people felt about providing care from 1 (negative feelings) to 10 (positive feelings), unpaid carers in our survey tended to be happy, with a mean score of 7.1 (Jitendra et al., 2024, forthcoming).

Digging deeper, we asked both unpaid carers and parents who provide the bulk of care for someone to tell us why, and the frontrunning reason for both groups was that they wanted to, 46% of unpaid carers and 40% of parents said this. Only a minority said they provided most of the care for someone because paid care services were too expensive, 15% for unpaid carers and 18% for parents.

Additionally, the relationship between informal and formal care is complex. It is not true that increased availability of unpaid care necessarily means a comparable reduction in the need for, or use of, paid care services. Researchers have found that even when people draw on formal care services, there is still a need for unpaid care, for example to liaise with care workers for someone with high care needs. One US study found that more formal care hours were not associated with any reduction in informal care hours undertaken (McMaughan Moudouni et al., 2012).

Research from Scotland, where personal care has been free for over 65s since 2002 and all adults since 2019, found that the presence of unpaid carers could actually increase the use of paid care services in the short term as unpaid carers helped cared-for people access their entitlements (Lemmon, 2020). More broadly, care needs can also be volatile and changeable. As Emily Kenway, an author and unpaid carer writes, illness can be ‘lawless’, meaning the often mechanistic routine through which paid care services are delivered is unlikely to meet every care need (Kenway, 2023).

This points to a need for more unpaid care as well as an expansion in paid care services. PSSRU estimated in 2018 that the number of disabled older people receiving unpaid care is projected to increase from 2.1 million in 2015 to 3.5 million in 2040, with more disabled older people projected to receive care from their partner than their child. This includes people with a range of care needs, from intense and full-time to low-intensity (Wittenberg et al., 2018).

Using data from Understanding Society and demographic growth estimates, we estimate that there will be 400,000 more people caring for elderly, sick or disabled people for 10 hours or more in the UK by 2035. This represents an 11.3% increase overall. If we broaden our scope to include low-intensity carers (0–9 hours), this grows to an additional demand for unpaid carers in 2035 reaching 990,000, 10.6% higher than now. In total, the projected number of high-intensity carers needed by 2035 is 4 million and for all carers is 10.3 million. It is likely that unmet care needs would also continue to rise alongside this, given that the proportion of over 65s in the population is growing faster than the average.

While the largest projected increase in unpaid carers is amongst the over-65 population, there is due to be a marked increase in the number of working-age people caring for elderly, sick or disabled people, with 130,000 more working-age people caring for 10+ hours by 2035. This rises to 350,000 if you include all carers. This is likely to present a challenge to the labour market, with 2.7 million working-age people undertaking more than 10+ hours of unpaid care by 2035.

The projections for parent carers show a more complicated view. Low birth rates between 2012 and 2022 means there are fewer children to care for, despite a recent uptick in birth rates. Our analysis suggests that by 2035, there will be 7 million parents caring for children under 14, compared with 7.2 million now.

Care needs are getting more intensive and long-running

Changes in the health of the nation will also have an impact on caring needs. The NHS’s Personal Social Services Survey of Adult Carers in England for 2023–4 which surveys over 200,000 carers found carers primarily supported people with physical disabilities, long-standing illnesses, dementia and problems with ageing.

We are already seeing changes in the needs which carers are meeting suggesting the demand for care is in flux. For example, more carers were caring for someone with dementia, a mental health condition or a learning disability in the last 10 years, while fewer were supporting those with a physical disability or problems connected to ageing (NHS England, 2024).

How could these changes affect the type of care we need?

The nature of different health conditions affects the type of care needed to manage them:

- Learning disability can create very long-term and intensive care needs. Research with carers has found that the majority of carers looking after adults with learning disabilities had been doing so for over 20 years (NHS England, 2022).

- The projected increase in the prevalence of dementia will necessitate more intensive and long-term care needs, some of which will need to be met by an increase in paid care services but much of which will likely need to be met by unpaid carers.

- An increase in the prevalence of diabetes could necessitate more specialised knowledge about medication and treatment to manage the condition, as well as care needs which can arise unexpectedly or suddenly if the disease is not yet diagnosed.

- Increases in the prevalence of anxiety and depression, the most common mental health conditions, will likely require both more high-intensity care, and care which can meet unexpected needs, given the sometimes volatile nature of these conditions.

We can see that the intensity of care needs is already changing. The number of full-time carers (those caring over 35 hours per week) is increasing sharply while other types of carer remain broadly steady. Low-intensity care (0–9 hours per week) makes up the bulk of care frequency but has also remained stable.

An increase in the number of high-intensity carers poses significant questions for policy-makers, these carers’ ability to work is severely curtailed, and largely their individual incomes will come from savings and benefits. This points to a need for a benefits system which offers carers dignity and protection from hardship, over the potentially long periods they may need to draw upon it.

3. Will the supply of care, and carers, keep up?

Care needs are growing and changing, but we are not currently meeting these needs, and we could struggle to meet them in the future without policy change. For paid care services, affordability and availability remain barriers to people taking up formal care, there are 400,000 people waiting for a care needs assessment or for their care to begin and the cost of care can be a strong disincentive to access it (ADASS, 2024).

High vacancy rates in the adult social care sector persist despite overseas recruitment (Bottery and Mallorie, 2024), and there are concerns that the planned childcare expansion will be scuppered by an inability to recruit workers (Hardy et al., 2023). There are also significant gaps in sufficiency of formal, paid childcare services, especially for children with special educational needs (Hodges et al., 2024).

Changing norms in gender and work

The number of people undertaking unpaid care, and their capacity to care, is also reducing. Historic gender norms mean women still make up the bulk of unpaid carers. Our analysis of Understanding Society data from 2010–2022 shows that in the UK women make up 61.8% of carers caring for more than 10 hours per week, with men making up 38.2%.

But these norms are, rightly, changing, there are more women in the labour market (Francis-Devine and Hutton, 2024), either because they want to work or because families today often need two incomes to prevent financial hardship and insecurity (Cribb et al., 2017). While labour market inactivity due to caring for an adult has remained broadly stable, it has reduced for those caring for a child, as more women are employed and birth rates have reduced in the last decade (Ring et al., 2024).

But even as more women work, they remain the likely primary carers in a household, both for adults and children. Our analysis of Understanding Society found that in the last 10 years, men and women’s caring patterns remain broadly unchanged in the UK, with women significantly more likely to be undertaking unpaid care for a sick, elderly or disabled person (see Figure 6). While we cannot get comparable data for parents from Understanding Society, Figure 7 shows, using recent data for the UK, that women are providing more childcare, even as more mothers are in the workplace.

Finally, we find that there are more people with caring responsibilities in the UK, both those caring for adults and children, in work than before. Figure 8 shows that this is particularly the case for parents, whose rates of employment participation have increased by 14% points from 2010.

Taken together, this means that even as birth rates have declined and there may be less demand for childcare, the supply of carers is also curtailed because fewer women are available to do it.

Some of this unmet need will be met by paid care services — this is especially true in early years education and childcare, where working parents of very young children will become eligible for subsidised childcare from this autumn. However, young children need round-the-clock care, and research suggests placing young children in full-time childcare long term could have negative developmental impacts (Erickson, 2018). This points to the need for more unpaid care capacity needed, not solely paid care. For adults needing long-term care, there is no planned expansion of subsidised social care planned to meet the demand for care created by changing gender and work norms.

Higher demands for care need new solutions. We should not assume women in families will pick up the burden of care, and should recognise that the financial penalty for doing so is increasingly more consequential. That more carers, of both adults and children, are engaged with the labour market, and that this trend is likely to continue, suggests that reforms which help people care and work will be central to meeting the changing demand for care.

4. Building caring systems for the future

There are 2 actions policy-makers will need to take to meet the growing and changing demand for care. The first is trying to reduce the demand itself by helping people live healthier lives for longer: for example, while care needs in childhood and old age are inevitable, the severity of care needs can be reduced through interventions to reduce the prevalence of preventable diseases. This should be an important part of government policy but is not the focus of this paper.

The second action is to meet this demand, ensuring there is sufficient, appropriate care so care needs are met and managed. These can be met through paid support, such as domiciliary care, childminders and childcare providers, or through unpaid care in family or other social networks. There is ample evidence that paid care services will need to scale up to meet growing demand. Our analysis finds that there will also be an increase in the number of unpaid carers in our society, both working-age and older carers. The type of care people do is also changing, with more people caring full time, and for longer, as chronic and degenerative conditions increase in prevalence.

Millions of people are already having to make deeply personal and difficult decisions about how to meet their own or their loved one’s care needs, a decision often between a significant financial hit to draw on paid care services, or a significant financial hit for them or a loved one to leave work to care. As the health and makeup of our country changes, more of us will have to make these difficult decisions. The best way to give people choice and freedom is to ensure that both paid care is available and affordable, and that unpaid carers can live with dignity and financial security.

This is not the system we have today. Both our paid care systems and our support systems for unpaid carers are inadequate to meet the needs of current carers and cared-for people, let alone meet the growing and changing needs of a future where we live longer while having less time to care ourselves. Paid care services are often unaffordable, scarce, of variable quality and questionable value to the taxpayer, and face existential workforce pressures which disempower and devalue workers. We find that gender, demographic and working norms mean that we can be less sure there will be enough people willing to care themselves, particularly given the financial impact. There is already evidence that we are facing a shortfall of adult children caring for their disabled older parents (Pickard, 2013).

We have arrived at our current system after years of piecemeal improvements, and in some cases inaction. Changing the status quo will require government to use both old and new tools, improving systems independently while redesigning how they interact.

A whole system approach to meeting care needs

There are 4 key domains central to meeting current and future care needs, paid care services, the benefits system, job design and social networks, all of which need to be in the view of policy-makers. These need to be improved independently so each can be a strong pillar to support people who need and give care, but planned and designed together because the objectives with respect to supporting carers are shared.

This inter-relatedness arises from the reality and ‘lawlessness’ of health, and so should be designed into any policy response. But it also could be a positive characteristic of the system, because weaving together different elements of the system to support people is a better way of giving people care that actually meets their varied needs.

Paid care services are the subject of most of the debate about meeting increasing care needs. To do so, they will need to be available, affordable and appropriate — but right now they are marred by high vacancy rates and costs, delays and sufficiency gaps. In early years childcare, the Government is mid-way through a significant expansion of subsidised formal services where funding on the system will increase by 49% in just one year (National Audit Office, 2024).

In adult social care, progress has stalled on a new settlement to make care services more affordable. The Labour Government has ruled out planned reforms to put in place a lifetime cap on the cost of care, but has committed to mandating higher pay for care workers, which could drive up the supply, quality and availability (and potentially user fees). Labour has also promised to create a National Care Service, which could establish a national set of standards for the currently fragmented adult social care sector.

Meeting growing and changing care needs requires workforce strategies which drive up pay and conditions in paid care sectors, higher minimum standards in return for public funding, progress on expanding subsidies and a drive to make care appropriate and personalised for a range of needs. Taken together, these will give many more people the choice and incentive to take up formal care services and move the burden of care from individuals and households to providers and the state.

The benefits system supports a huge number of people doing unpaid care, including unpaid carers of sick, elderly and disabled people and parents with dependent children, to replace some lost wages and help cover the additional costs of caring. Most parents receive Child Benefit, while low-income working-age households receive additional support through the Universal Credit child element and Child Tax Credits. Universal Credit varies depending on an individual’s income. Unpaid carers receive Carer’s Allowance, while the poorest can claim Universal Credit and Pension Credit with additional carer top-ups. The number of people caring on Universal Credit and carer benefits is forecast to rise (Department for Work and Pensions, 2024).

Despite this, families with children and unpaid carers are disproportionately more likely to be in poverty than the general population (JRF, 2024) and unpaid carers increasingly feel unable to look after their own wellbeing (NHS England, 2024). Labour’s promise to refocus the Jobcentre Plus to support people into work is welcome, as is the Government’s commitment to a child poverty strategy, broader review of Universal Credit, and action to tackle overpayments under Carer’s Allowance. However, the growing number of long-term, high-intensity carers means more people will be relying on the benefits system for longer while they care, and incomes need to be adequate to prevent them falling into poverty. At a minimum, the benefits that carers rely on should cover the costs of essentials and additional costs associated with caring. This means reviewing the value of the Universal Credit standard allowance and child elements, and Carer’s Allowance and carer top-ups to means-tested benefits like Universal Credit, Income Support and Pension Credit.

Increasingly, work and job design play a crucial role in enabling, or preventing, people from making the right choice about whether to care themselves or not. While there is some support available to help parents balance work and care — namely flexible working arrangements and paid parental leave — these are insufficient, with low take-up of shared parental leave and a culture of work where flexible working is not built into job design. There is significantly less support for people caring for elderly, sick or disabled people, beyond voluntary compassionate leave from employers and a new entitlement to 5 days of unpaid care leave. We know there is a significant financial penalty for people leaving work to care, with mothers facing a pay penalty of over £21,000 six years after leaving work to care, and unpaid carers facing a pay penalty of nearly £8,000 after the same period.

Some change has already been promised, Labour has committed to making parental leave a day one right for new workers and flexible working a default, and want to establish a Fair Work Agency to enforce employment rights. This will be an important first step, but without an expanded paid care leave offer, people will find themselves foregoing significant amounts of pay and risk facing poverty. JRF has called for a new Statutory Care Pay entitlement to be created, which would cover a proportion of a worker’s pay for 9 months over the course of their working life while they cared full time, and has also called for an increase in generosity in paternity leave. There should also be a long-term ‘right to return’ entitlement which allows people to take 12 months of unpaid leave with a guarantee of returning to their old job.

Finally, social networks and other support offers crucial, often hidden support for cared-for people. Grandparents can be a crucial help to keep paid childcare costs down. We found that services like cleaners and handymen met care needs instrumentally, despite them not being seen as ‘paid care services’. Social networks like neighbours and friends can also meet these needs and help cared-for people remain connected and offer emotional support. But these relationships can arise at random and some, like renters who are not rooted in place, families who live far from other relatives, or elderly people with mobility issues who do not socialise often, are not able to rely on these networks.

Hilary Cottam sets out one way the state could seek to engender and amplify these relationships, by creating ‘circles’ of neighbours who offered to help people needing support in their local community, from help around the house to picking people up from hospital appointments. Anyone could be a member and offer help, including people needing help themselves. Operating in 10 areas with 10,000 people helped, these groups seemed to have an impact on the wellbeing of the community, with a significant reduction in local hospital admissions (Cottam, 2018). Apps like NextDoor, where neighbours can share tips and sell unwanted items, or jointly, where carers caring for the same person can coordinate, point to digital tools which could build and sustain these networks. To really make an impact, local government should support and seed local networks of this kind.

Embedding and co-planning system change

We draw upon different kinds of care to meet our care needs and require a range of support to meet complex and sometimes changing needs, yet systems themselves do not often interact. Figure 9 sets out how these systems could inter-relate more dynamically.

More generous benefits can act as an incentive to undertake unpaid caring. Given the future of the care system will depend heavily on the availability, and wellbeing, of unpaid carers, we should see carer benefits as part of the National Care Service.

Work and benefits should integrate for carers, for example, many carers want to work but are restricted by an earnings limit in Carer’s Allowance. Government needs to ensure working-age carers can benefit from tapered benefit income, either through a redesigned Carer’s Allowance payment, or by ensuring eligible carers are claiming Universal Credit.

The National Care Service could better personalise care by embedding local ‘circles’ which offer emotional and manual support for people needing help. In childcare, this could include cooperative models of childcare where parents undertake care for their children and others in a rota.

A Future Care Needs Taskforce

Without a change in direction, rising care needs risk overwhelming our outdated and fragmented systems.

To meet these complex and growing needs as part of a cross-departmental and joined-up strategy, Government should set up a new Future Care Needs Taskforce for England. This would collectively plan how to meet these needs in different domains, being mindful of how these systems can interact to best support those needing care and those undertaking it. This would likely also save the taxpayer money. While the relationship between take-up of paid and unpaid care is complex, we can reasonably say that in the long run it is cheaper to meet care needs through unpaid care and paid care services than through paid care services alone.

Government should set the scope of the taskforce, like that of the Child Poverty Taskforce, to set the overall strategy and goals for meeting growing and changing care needs, this could be limited to planning how to meet care needs, or have a broader remit to also work to reduce care needs where possible.

The Taskforce should be set up by the end of 2024 and chaired by the Secretary of State for the Department for Health and Social Care with ministerial representation from the Department for Work and Pensions, the Department for Business and Trade, the Ministry of Housing, Local Government and Communities and the Department for Education and regular discussions with devolved governments, with the potential to include Public Health England if the remit of the Taskforce includes reducing care needs. This Taskforce should be able to commission research to set out the demand for different kinds of care and how we might meet them, consult with stakeholders, plan interventions, and make policy recommendations to government ahead of the 2025 Spending Review. When strategy has been decided, it should report to the Health Mission Delivery Board every 6 months.

The Government has a unique opportunity to build a system capable of turning the tide and offering an exemplar to other countries facing the challenges of a changing society. But it is only through this cross-governmental collaboration that we can meet one of the greatest challenges our nation, and the world, faces.

Method

This section is a summary of the assumptions and approaches used:

- definitions for the key variables from Understanding Society dataset

- rationale for the projections of carers in 2035, including methods discounted in favour of the chosen approach.

Definitions from variables using Understanding Society (USoc)

- We define higher intensity unpaid carer as anyone who cares for someone inside (aidhh) or outside the household (aidxhh) and cares for 10 hours or more (aidhrs), and also excluding the category 'Varies, but under 20 hours'. We chose not to apportion respondents of this group proportionate to the other 0-20 hours groups.

- Unpaid carer is defined as anyone who cares for someone inside or outside the household and cares for any number of hours.

- We create a custom cross-sectional weight conditional to each wave of the survey to account for the different weighting variables. We use cross-sectional weights as we want proportions at the time of response and are not tracking respondents across the waves.

- We also created custom demographic variables for ethnicity (racel_dv), sex (sex_dv), and age band (dvage).

- We use jbstat to understand work status at the time of wave. We align employment with FRS and consider employment to include parental leave, temporary working arrangements and apprenticeships.

- We define 'parent' using the nchresp variable. We use this variable as a proxy for intensity, as this variable denotes responsibility for children where nchild_dv does not. We recognise the limitations of this chosen variable due to it defaulting to female caregivers.

- We define needing formal help as being 65+, having an ADL or IADL (adla-adln) and accessing formal care services (hlpforma – hlpformb). We consider conventional formal care to include support from a home care worker, care staff team or nurse. We consider unconventional formal care to include sheltered housing manager, cleaners and other groups.

We use additional datasets to support our findings from USoc, in most cases where we were unable to find the right data in USoc or where sample sizes are too small or where we did not need 13 years of data.

- We use the Department for Education’s Parents Survey, Additional Tables for data on usage of formal childcare for 0-14 year olds.

- We use ONS Time Use Survey data to illustrate time spent on childcare by sex.

- We use the NHS Personal Social Services Survey of Adult Carers in England for 2023-4 to find out what illnesses unpaid carers primarily supported people with.

Projections

In order to project numbers of future carers, we combine USoc data for our definitions of carers with ONS population estimates and projections.

We first calculate weighted proportions of unpaid caring by 5 year age band and sex in each wave of the USoc data, and match this to ONS population estimates data using the nomis data portal. We add to this the ONS’ principal projections data (ukpppsumpop) forward to 2035.

We then calculate care rate averages by age band and sex for the 13 years of USoc data, and apply these averages to the population estimates and population projections data to get a smoothed set of population numbers of carers by age band and sex from 2010-2035.

Our approach leads us to a conservative and largely population driven increase in the number of unpaid and higher-intensity carers.

Amongst the considerations for projecting number of carers forward were more formal modelling approaches. One used a basic time series forecasting approach, using a Damped Holt method to estimate the care proportions per age band and sex to 2035, using the trends in the previous 13 years of data. This approach was discounted because the yearly variance in care proportions by age band and sex created a large confidence interval for the central forecast.

The second method we considered was fitting an ARIMA model to the care proportions, using age band, sex and population estimates as external regressors, to forecast future values of care proportions up to 2035. This approach was discounted as we were not confident that our choice of regressors fully captured the complex relationship between care proportions and the population.

The choice to explore alternative modelling approaches stemmed from our understanding of the importance of time to caring, per the age bands, sex and population. In future we may explore this option further.

References

ADASS (2024) 2024 Spring Survey

Bottery, S. Mallorie, S. (2024) Social care 360: workforce and carers

Cottam, H. (2018) Radical Help

Cribb, J. Hood, A. Joyce, R. Norris Keiller, A. (2017) Families dependent on fathers' earnings alone have average incomes no higher than 15 years ago

Department for Work and Pensions (2024) Benefit expenditure and caseload tables 2024

Department for Education (2024) Childcare and early years survey of parents

Erickson, J. (2018) Measuring the Long-Term Effects of Early, Extensive Day Care

Fenton, W. Polzin, G. Fleming, N. Fozzard, T. Price, R. Davison, S. Holloway, M. Liu, H. O’Gara, A. (2023) The state of the adult social care sector and workforce in England

Francis-Devine, B. Hutton, G. (2024) Women and the UK economy

Hackney.gov.uk (2023) Four primary schools in Hackney will close next September due to the ongoing decrease in the number of school-aged children

Hardy, K. Stephens, L. Tomlinson, J. Valizade, D. Whittaker, X. Norman, H. Moffat, R. (2023) RETENTION AND RETURN: Delivering the expansion of early years entitlement in England

Hodges, L. Shorto, S. Goddard, E. (2024) Childcare Survey 2024

Hu, B. Hancock, R. Wittenberg, R. (2020) Projections of Adult Social Care Demand and Expenditure 2018 to 2038

Jitendra, A. Woodruff, L. Thompson, S. (2023) The caring penalty

Joseph Rowntree Foundation (2024) UK Poverty 2024

Kenway, E. (2023) Committing a benevolent insult?

Kingston, A. Wittenberg, R. Hu, B. Jagger, C. (2022) Projections of dependency and associated social care expenditure for the older population in England to 2038: effect of varying disability progression

Lemmon, E. (2020) Utilisation of Personal Care Services in Scotland: The Influence of Unpaid Carers

McMaughan Moudouni, D.K. Ohsfeldt, R.L. Miller, T.R. Phillips, C.D. (2012) The Relationship between Formal and Informal Care among Adult Medicaid Personal Care Services Recipients

National Audit Office (2021) The adult social care market in England

National Audit Office (2024) Preparations to extend early years entitlements for working parents in England

NHS England (2022) Personal Social Services Survey of Adult Carers in England, 2021-22

NHS England (2024) Personal Social Services Survey of Adult Carers in England

Office for National Statistics (2022) Voices of our ageing population: Living longer lives

Office for National Statistics (2024) statistical Population estimates bulletin

Office for National Statistics (2024) statistical Population projections bulletin

Office for National Statistics (2024) Time Use Survey

Pickard, L. (2013) A growing care gap? The supply of unpaid care for older people by their adult children in England to 2032

Raymond, A. Bazeer, N. Barclay, C. Krelle, H. Idriss, O. Tallack, C. Kelly, E. (2021) Our ageing population: how ageing affects health and care need in England

Ring, K. McCurry, H. Colthorpe, R. Rawlings, J. (2024) Trends in labour market inactivity for caring purposes

University of Essex, Institute for Social and Economic Research. (2023). Understanding Society: Waves 1-13, 2009-2022 and Harmonised BHPS: Waves 1-18, 1991-2009. [data collection]. 18th Edition. UK Data Service. SN: 6614, http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-6614-19

Watt, T. Raymond, A. Rachet-Jacquet, L. Head, A. Kypridemos, C. Kelly, E. Charlesworth, A. (2023) Health in 2040: projected patterns of illness in England

Wittenberg, R. Hu, B. Hancock, R. (2018) Projections of Demand and Expenditure on Adult Social Care 2015 to 2040

This briefing is part of the care topic.

Find out more about our work in this area.