We must act on AI literacy to protect public power

Tania Duarte, Founder of We and AI and Ismael Kherroubi Garcia, Founder and CEO of Kairoi argue that current artificial intelligence (AI) narrative concentrates elite power, restricts policy debates, and limits public engagement. And it’s developing fast. So it's vital the UK develops a public education strategy quickly with civic society and in collaboration with, but not dictated by, technology companies.

We are increasingly aware of the role of artificial intelligence (AI) in our lives. In 2023, Collins Dictionary selected ‘AI’ as the ‘word of the year’, but this increased awareness does not mean that we are necessarily more knowledgeable about AI (Harris et al., 2023). Given the rise of uninformative, hyperbolic, and polarising narratives about AI, increasing AI literacy amongst the public becomes even more paramount.

AI literacy encompasses the varied skills required to understand, analyse, and evaluate the uses and impacts of AI technologies. These skills should not be developed through a solely technical lens, instead AI literacy programmes must also consider the social implications of such technologies. Despite the need for people to know and understand AI, and how such technologies pertain to their everyday lives, there is a notable absence of AI literacy initiatives delivered here in the UK.

Improving AI literacy, however, would strengthen public voice and power, allowing more ordinary people to meaningfully engage with AI advancements, applications, and implications.

AI literacy and narratives – restricting policy and public attitudes

At a foundational level, the public at large should be able to know and understand AI concepts. However, the absence of a concerted effort to enhance AI literacy in the UK means that public conversations about AI often do not start from pragmatic, factual evaluations of these technologies and their capabilities. Instead, debates tap into shared cultural memories developed through mythology, folklore, literature, art and performance (Kherroubi et al., and Craig et al., 2018). The science fiction genre, for example, offers a natural reference point in providing shared cultural associations, which fill in the gaps when facts about AI are not available. Such narratives shape our values, beliefs, and assumptions about AI advancements and policies.

Theory about narratives’ influence on policy is well-established (Davidson, 2016, and Furze, 2023), and their role in tech policy is gaining salience. (Matthijs Maas, 2023) articulates why and how metaphors and analogies matter to both the study and practice of AI governance. He describes the difficulties encountered when, as put by (Crotoof and Ard, 2021), shorthands ‘gloss over critical distinctions in the architecture, social use, or second-order consequences of a particular technology, establishing an understanding with dangerous and long-lasting implications.” Maas identifies specific AI challenges, such as the role of selected analogies in advancing regulatory efforts, providing misleading information and limiting our understanding. Given the speed of AI developments, the lack of widespread factual knowledge is hardly surprising. However, such gaps in public knowledge do present opportunities to blur realities and/or influence policy amongst those who understand the power of narratives and have the resources to leverage them to drive their agendas (Weiss-Blatt, 2023).

The relationship between AI literacy and AI narratives can also be seen in public attitudes work. In 2023, the Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation’s (CDEI) data and AI public attitudes tracker asked respondents to identify the greatest risks of AI use in society from a list of nine options. The top 3 risks selected were that ‘AI will take people’s jobs’ (45%), ‘AI will lead to a loss of human creativity and problem-solving skills’ (35%), and ‘humans will lose control of AI’ (34%). The risks proposed by the CDEI clearly limit what the public can state about AI. Respondents were not, for example, given an opportunity to express any concern about increasing environmental damage caused by AI development; this therefore cannot be documented as a public opinion, restricting its influence on policy and wider debate. Available responses can, however, be linked to common AI narrative traps – anthropomorphising AI, elevating AI tools to having human-like status, and prioritising the ‘existential risk’ narrative symptomatic of widespread marketing and lobbying efforts (Weiss-Blatt, 2023). Without efforts to raise AI literacy, official public opinion is likely to remain entwined with narrow, and often harmful, narrative framings.

AI literacy frameworks

Whilst AI tools may be perceived as novel phenomena, literacy initiatives are not. Rather than starting from scratch, developing credible AI literacy initiatives can draw from existing frameworks and methods. There is a long history of literacy frameworks, including information literacy, media literacy, digital literacy, and data literacy (see, for example, the DQ Institute’s). Such well-established pedagogical methodologies feed into the development of effective educational content and courses.

Yet, AI literacy competencies diverge from those of traditional IT or technology literacy due to the ‘unique facets of AI: autonomy, learning, and inscrutability’. Instead, AI literacy requires a sociotechnical perspective - considering both social and technical aspects of AI systems - because ‘AI practice is interdisciplinary by nature, and it will benefit from a different take on technical interventions’.

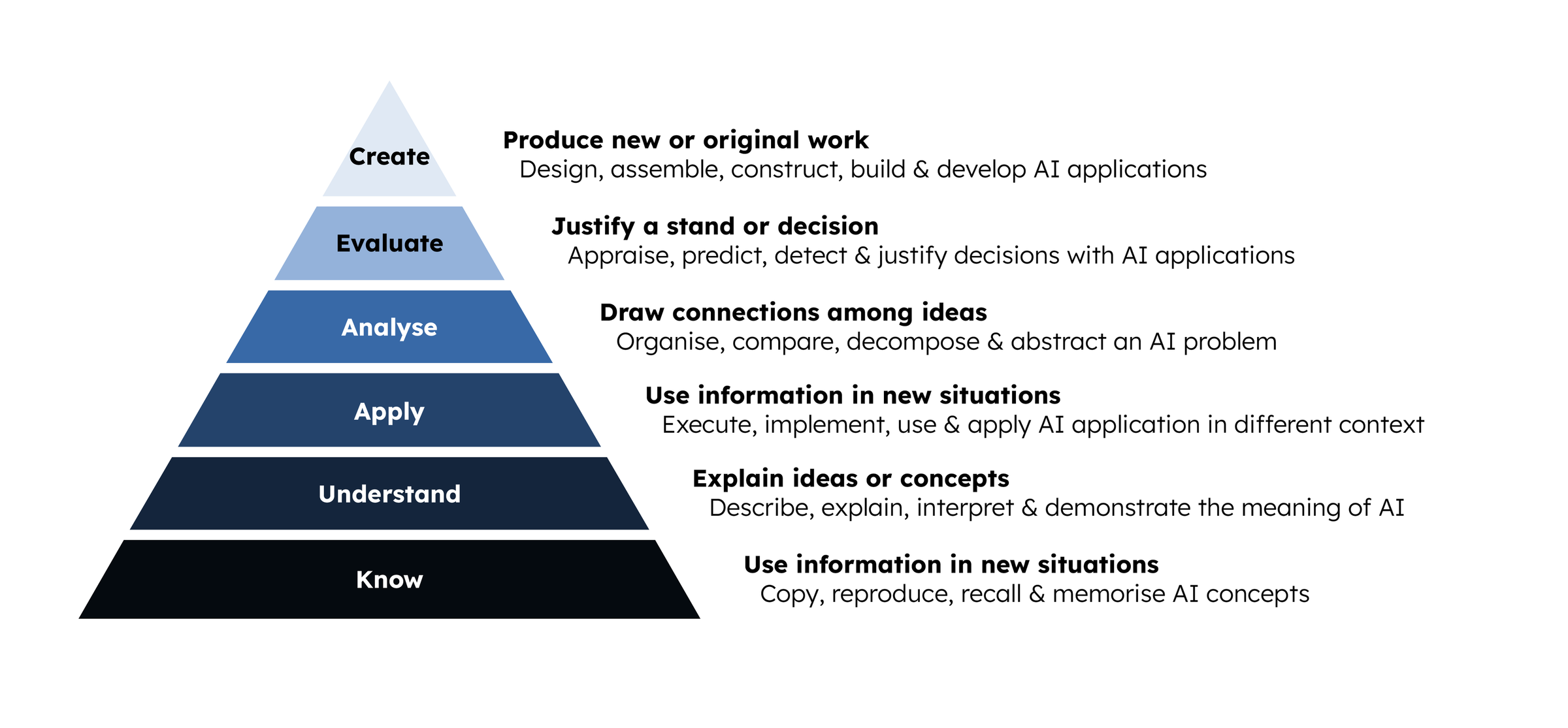

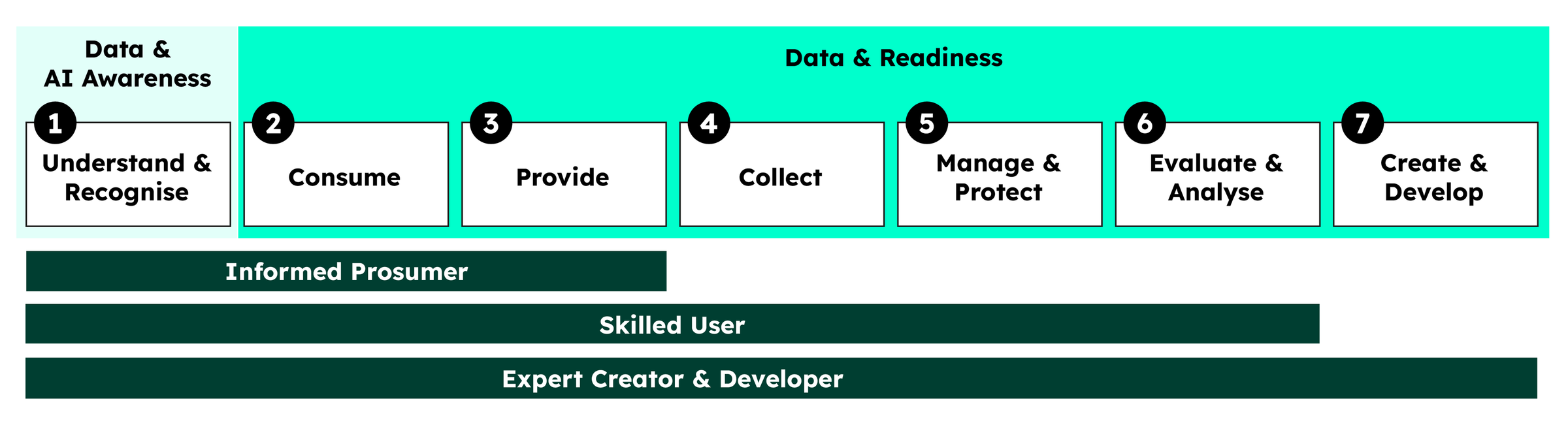

Many AI literacy frameworks have been, and are continuing to be, developed. In a review of 30 articles, Ng et al suggest a model of categorising AI literacy (Fig. 1); the 6 segments represent increased literacy levels from the most basic – ‘knowing’ AI, to the most advanced – ‘creating’ AI (Ng et al, 2021). This framework suggests that the ‘know’ and ‘understand’ levels of should be widely attainable and measurable. In a further mapping of AI and data literacy levels by Shüller et al (Fig. 2), an informed public should attain the first 3 levels of ‘understand and recognise, consume and provide’ (Shüller et al, 2023).

It is clear, therefore, that existing and developing frameworks provide effective ways to categorise and measure AI literacy; such theoretical frameworks must, however, be combined with practical action on a local and national scale.

AI literacy around the world

Whilst AI literacy is still an emerging field of practice, courses have been created globally to enable a greater public understanding of AI. In 2019, the University of Helsinki developed a free course aimed at training 1% of EU citizens in the basics of AI. In 2021, UNESCO's inaugural global standard on AI ethics was adopted by all 193 Member States, including the UK. One of its ten core principles is to promote public ‘Awareness and Literacy’ around AI and data. Through open education and informed by civic engagement, their approach aims to ensure the effective participation of all members of society in conversations about how they use AI, how AI systems affect them, and how to protect themselves from undue influence.

In the US, there are several funded initiatives run by non-profits to increase AI literacy in communities and education settings. Furthermore in 2023, the National Intelligence Advisory Committee produced a report on Enhancing AI Literacy for the United States of America. Recommendations include creating a National AI Literacy Campaign, investing in formal educational or learning frameworks alongside informal learning opportunities. This was followed by the introduction of a bipartisan Artificial Intelligence Literacy Act.

The Scottish Government also made commitments to improve the public’s understanding of how AI is already impacting their lives and society. We and AI worked with them to create a free online course - Living with AI, written for the average reading age in Scotland.

However, there have been no nationwide initiatives in the UK to increase AI literacy. The UK AI Council’s roadmap did advise on specific measures; yet the National AI Strategy developed from its recommendations excluded all those related to public AI literacy. The lack of credible and accessible national AI literacy initiatives has led to a reliance on resources from tech companies with vested interests in presenting AI in a commercially attractive light. Such market domination allows tech companies to frame AI in techno-solutionist, deterministic, or unambiguously optimistic ways, reinforce misleading AI narratives, and convert learners into customers via marketing strategies (Duarte and Barrow, 2024). This urgently needs to change if we are to collectively reap the benefits of improving AI literacy – tipping the power towards public and civic power, over private profit.

AI literacy and public power

AI literacy is inextricably entwined with the public’s voice, as well as their access to, and scrutiny of, power. As per Ng et al.’s AI literacy pyramid, if the public had, as a minimum, significant knowledge and understanding of AI technologies that are embedded in our lives and in policy (Kherroubi, 2024), they can begin to ‘recall AI concepts’ and ‘explain, interpret and demonstrate the meaning of AI’. These most basic levels of literacy begin to build within the public, what Schüller and colleagues describe as, ‘not only a tool set or skill set, but above all a mindset: to critically question the quality of data and information sources; to be able to separate facts from opinions; to recognise the limits of data, including the capabilities and limits of AI applications and algorithms. And to make the right decision based on this recognition’.

Improving AI literacy supports the ability to decode narratives and make informed, values-based decisions. Agency and decision-making relate to individuals as consumers of AI products and services, as employees or union members, or users of public and private services. The public’s ability to understand AI ideas and concepts (separate from their capacity to apply or use the tools directly) is therefore linked to voice, agency, and power. Power gained through improved literacy can be exercised in cause-based activism and movement building. This can consequentially lead to successful legal challenges, such as the Home Office dropping of a discriminatory algorithm or the U-turn on grading A-levels by algorithm during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Evidence also suggests that improving literacy enables engagement in deliberative democracy or political lobbying. A study of a media literacy program revealed that it contributed to adolescents’ intent toward civic engagement. According to UNESCO, media literacy education can also result in increased citizen participation in society. We might suppose, therefore, that AI literacy programmes could also positively impact civic and democratic participation – an urgent antidote, perhaps, to the threat that AI may weaken and undermine democratic processes.

To conclude, current mainstream AI narratives do not build literacy amongst the public. Rather, they can concentrate elite power, restrict policy debates, and limit public engagement. The UK must show the same commitment as other countries to national AI literacy; it should develop a strategy in conjunction with civil society – one in collaboration with, not dictated by, technology companies. Any AI literacy programme must reflect the social practices and implications, as well as the technical aspects of these technologies. The frameworks are available, and the benefits are proven. With AI developing at an alarming rate, we cannot delay in ensuring the public are adequately literate and meaningful engaged in how these technologies shape society.

This reflection is part of the AI for public good topic.

Find out more about our work in this area.