Artificial intelligence for public good

As JRF launches a new artificial intelligence (AI) project, Yasmin Ibison outlines its aims and the key questions it will explore.

Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral

Following on from last year’s Social Justice in a Digital Age work, JRF is launching a new project on the potential for AI to generate public good. This is another example of our work platforming original thinking in response to deeper, cross-cutting issues related to our mission. Rather than delivering traditional policy programmes, this work-stream positions JRF as an inquisitive explorer – leaning into emergent and speculative work. Remaining ambitious, yet humble, our role is to convene relationships and commission content which builds and examines new ideas.

Bringing together a wide range of perspectives, from tech experts and public sector actors to not-for-profit organisations and grassroots groups, this project will examine ideas on the development and implementation of AI that creates public good. By public good, we refer to impacts or outcomes from AI that benefit the general public and are fairly distributed across society. Our aim with this project is to broaden and deepen existing AI debates - cutting through the hype of current mainstream narratives and legitimising and involving the voices of non-tech experts. We will explore both the practical implications of AI development for the public sector and civil society, alongside questioning the deeper moral undertones of AI advancement relating to values, power, and relationships. Rather than centring a singular perspective or advancing specific policy solutions, we will prioritise instigating conversations and building cross-sector connections to contribute to the growing social commentary on this topic.

The power of narratives

Type the phrase ‘AI will’ into Google’s (AI-powered) search engine and the predictions for the end of your sentence will likely oscillate from ‘destroy the world’ and ‘kill us’, to ‘save the world’ and ‘cure cancer’. Outside the bubble of tech researchers, developers and engineers, the ways in which mass narratives on AI are communicated can be over-simplified, surface level and polarising. For those of us with little or no prior expertise, it is easy to be seduced by the hyperbole. Discussions on the benefits and risks of AI are not new, on the contrary, in some circles they have been ubiquitous for quite some time. However, a recent resurgence of mainstream discourse on AI has generated two distinct, yet superficial, camps in the public sphere:

- Supporters (some of whom are tech investors) propose that AI will make us smarter, healthier, and happier. They proclaim positive examples of AI in healthcare diagnosis and scientific research, the potential for AI therapists, tutors, coaches, and artists, and most prominently declare that AI will drive up productivity in the labour market. Such techno-optimists may be blinded by the relative risks to AI development, relying on tech-first solutions to solve complex human problems.

- Sceptics focus on current and predicted existential and tangible risks - ranging from doomsday threats of death and human destruction to more rational challenges, including discrimination and algorithmic bias, job losses, environmental impacts, privacy concerns, tech monopolisation and effects on democracy. They may simultaneously emphasise the risks (often perceived as catastrophic), whilst downplaying any potential benefits. Such a techno-pessimistic approach may overlook the opportunities that harnessing AI could bring.

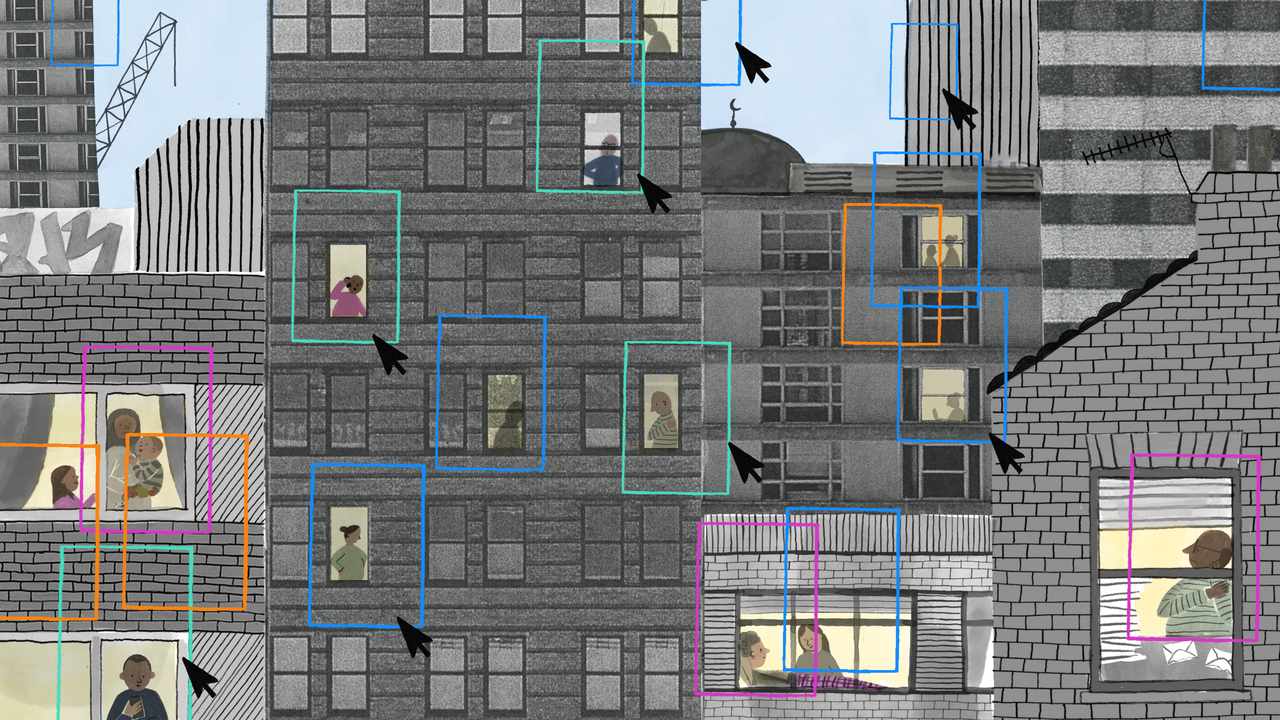

Consuming content that triggers utopic visions or moral panic about AI fails to provide the average person with sufficient tech expertise to contribute to more in-depth debates. This perpetuates a system whereby nuanced discussions on the development and deployment of emerging technologies mainly take place amongst the tech elite, further concentrating their power and influence. Yet AI has the potential to impact us all and there is immense value in democratising related discussions and decisions. Reinforcing a false binary of AI as a purely technological ‘good’ or ‘evil’ also does little to further our understanding of the real-world implications of such tools on individuals, communities, and the shape of society. As such, there is a real need to explore, critique and reshape existing AI narratives in the public sphere.

How can we ensure that mainstream narratives concerning AI build literacy, balance potential risks and rewards, and foster genuine public engagement?

AI in the public sector – crucial or controversial?

Whilst critiquing and shifting AI narratives is important to widen discourse, it will do little to slow down AI development. Huge sums of public and private money are pouring into accelerating these technologies and their application across the globe. AI tools are already changing how we interact with each other and corporations. Notably, as AI innovation accelerates, it has the potential to fundamentally shift how we interact with public sector services.

From health, social care and welfare, to employment, education, and financial support services, there are ample opportunities for AI tools to revolutionise public sector services. This includes from policymaking, operations, and service delivery perspectives. AI has already been embedded within some public sector services globally, including the UK’s Department of Work and Pensions. The Public Law Project launched a database earlier this year highlighting uses of AI by the UK Government to make or inform decisions on various policy areas - as of October 2023 there are 55 automated tools reported. Deployed in person-based predictive policing, at border controls, in welfare eligibility checks and to detect fraud, AI tools have the capacity to monitor, categorise and observe us, as well as predict our behaviour. However, some AI enhanced public sector services, such as the Dutch SyRi system, Denmark’s welfare algorithms, or the Polish unemployment profiling mechanism have already sparked significant controversy around lack of transparency, discrimination and human rights violations. Crucially, citizens are notably absent from decisions to embed AI in public services they use.

This begs the questions: What role should AI play in the public sector? How can we ensure AI adoption in public sector services generates public good? What values should drive the adoption of AI? What infrastructure, incentives, and guardrails are needed to support this?

AI and civil society - the silent voice?

Less is known about current AI adoption in wider civil society, including not-for-profit and grassroots organisations. Whilst such organisations lack the financial resource or compute[i] to build or procure large-scale AI themselves, they may still benefit from adopting free-to-use AI systems to support their operations. We won’t know the impact of AI in these spaces unless, or until, they begin systematically experimenting with available tools.

However, archaic systems and workforce digital skills gaps have often resulted in an inability of non-profit sectors to keep up with emerging technologies as they develop. Earlier this year, an audit of the Central Digital and Data Office (Central digital and Data Office, Transforming for a digital future: 2022 to 2025 roadmap for digital and data) revealed shortcomings within government departments seeking to close their digital skills gaps. Similarly, this year’s Charity Digital Skills Report (Amar and Ramsay, The Digital Skills Report) highlighted that many non-profit organisations still lack tech-based knowledge and infrastructure. While most are interested in the transformative potential of emerging technologies, they are not ready to respond to their development. The history of digital transformation in such sectors means large-scale AI adoption is unlikely to happen overnight.

Civil society’s role, however, includes delivering services for communities, engaging in advocacy, mobilising citizens, encouraging participation, and holding government to account. Regardless of whether such organisations choose to adopt AI tools, they cannot afford to remain silent in AI discussions related to their missions. Marginalised groups, many of whom will be beneficiaries of civil society organisations, may be those who are disproportionately impacted by the changes AI will make to society.

It will be interesting, therefore, to explore: what role should AI play in supporting civil society to generate public good? To what extent can AI support not-for-profits and grassroots organisations to achieve their missions – what infrastructure, cultures and ways of working would support this? How can civil society contribute to shaping AI developments?

Zooming out – AI, power, relationships, and values

Discussions centred on how various sectors should interact with AI – adopting new tools, changing organisational narratives, and embarking on advocacy – largely consider practical implications. Alongside these, we can also ruminate on deeper, values-based, or moral questions relating to the advancement of AI to generate public good.

Examining AI tools in relation to power structures and political economy draws out some interesting examples. There are AI tools branded as being ‘for good’ that have instead reproduced harm. Consider the humanitarian medical chatbots developed in the Global North, but implemented in the Global South, that replicated colonial power dynamics and Eurocentric views on mental health; or AI translation tools and AI lawyers that jeopardised asylum claims due to errors.

Such examples of AI disruption unearth questions of what value is created and for whom when AI tools are developed within market economies? To what extent does AI solely reinforce dominant power hierarchies? How might AI be used to weaken oppressive systems?

Without a clear vision of the type of world we wish to live in, it is also unclear how AI might help or hinder our journey to arrive there. Shifting our focus away from the technological tools themselves, and onto the systems and contexts that AI is built and operates within, opens up space to explore systemic or visionary questions. Imagine a future in which society has been fully disrupted by AI; AI tools are fully integrated across public and private life – within administrative and corporate services, public and frontline sectors, arts and culture, civil society, community groups and democratic processes.

How might the shape and feel of society have changed? How might our social contract, the relationship between citizen and state, and between public and private sectors have evolved? To what extent does this imagined future, triggered by AI disruption, align with our current social goals and values?

So, what’s next?

We are not claiming to be AI experts or to have all the answers, and as such, we will not be presenting a set of concrete policy proposals or clear blueprint for the future. We will be platforming a number of perspectives to stimulate debate, imagination, and creative thinking. We have already commissioned a collection of essays examining the impacts of AI narratives on literacy, digital exclusion, and public engagement – these will be published early next year. We will also be commissioning some research into the perspectives of not-for-profit and grassroots organisations on Generative AI. There will also be opportunities to attend events to discuss the ideas and insights from this work in more detail – watch this space!

If you would like to ask a question, challenge a viewpoint or simply find out more about this project, please get in touch with Yasmin via email: yasmin.ibison@jrf.org.uk, follow on LinkedIn or on X (formerly known as Twitter): @yasminibison

Note

[i]Computational power, or compute, is a core dependency in building large-scale AI; Computational Power and AI - AI Now Institute.

This idea is part of the AI for public good topic.

Find out more about our work in this area.