AI and countervailing power in the UK

Reflections, learnings and take-aways from JRF's November 2024 workshop, aimed at mapping and assessing sources of AI countervailing power in the UK.

What are we up against?

As AI technologies advance, there are growing concerns from many about the unprecedented concentration of power within a few large corporations.

Big Tech’s many levers of control are widespread: from embedding techno-solutionist narratives (the mindset that every problem can and should be solved with technology) to monopolising the data, compute and cloud services needed to develop AI tools. These large corporations also influence knowledge production through capturing talent and influencing research agendas.

Consolidating power in the hands of so few corporations has widespread social, economic and political impact, for example:

- large tech firms dominating markets and harming businesses and consumers by stifling competition and limiting innovation as they acquire or underprice start-ups, reducing consumer choice and raising prices

- deepening wealth inequality whereby enormous profits enrich shareholders, whilst workers are exploited, reap little benefit from their labour, and in some cases, risk job displacement.

- increased control over our information environment can influence public opinion, social dynamics and political outcomes, threatening to undermine trust and democracy.

As Meredith Whittaker, President of Signal, said in an interview last year:

"The more we trust these companies to become the nervous systems of our governments and institutions, the more power they accrue, the harder it is to create alternatives that honour alternative missions."

Building countervailing power, therefore, is key. Countervailing power refers to the forces that counterbalance or check the influence of dominant actors. To further explore countervailing power in AI, JRF designed a workshop bringing together AI experts from across 8 sources of countervailing power to:

- test ideas and reflect on countervailing power sources, their strengths and limitations

- identify opportunities for shared agendas, coordination and action

- broker conversations and build capacity between different actors within the AI ecosystem including government, civil society, media, academia, philanthropy and more.

The event was hosted and chaired by Gina Neff who is the Professor of Responsible AI at Queen Mary University of London, and Executive Director of the Minderoo Centre for Technology & Democracy at the University of Cambridge.

To begin, Gina stressed the need for the worlds of tech and AI policy to be working much more closely with social movement ecosystems. We must not think about AI in isolation, as a set of tools or processes, rather we should consider AI technologies as a form of social infrastructure that builds and shapes the world around us.

How can we better steward AI technologies towards creating a world where people and planet flourish? Power is central to this question, both the dominant power forces and those that countervail against them. Without considering power in relation to AI, we may be hurtling towards technologies that prevent such a world from ever emerging.

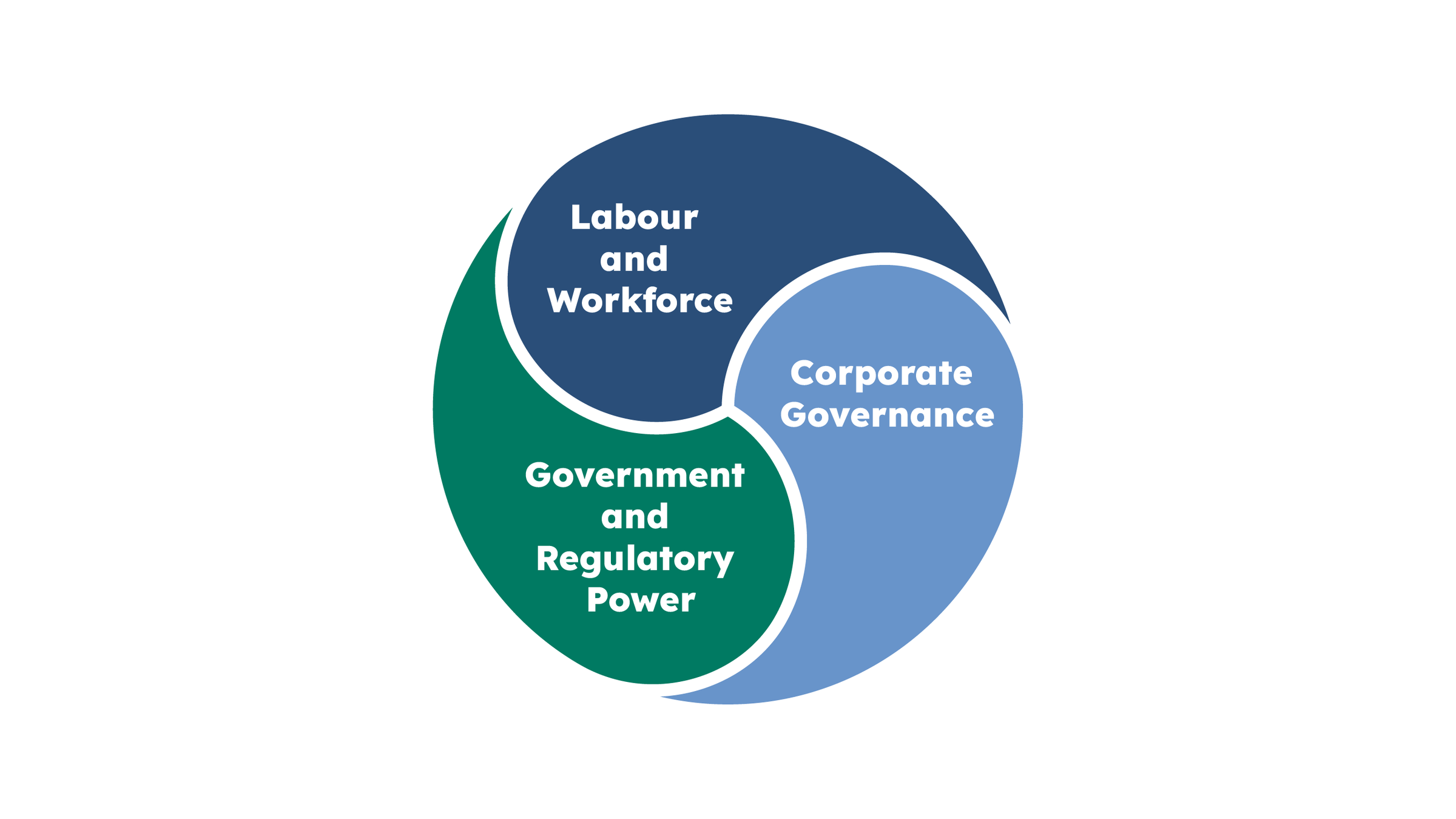

Sources of countervailing power in relation to AI

To stimulate discussion in the workshop JRF produced an initial list, by no means definitive, of countervailing power sources and their functions:

- Government and regulatory power: set legal boundaries, enforce compliance, and protect public interest.

- Civil society and public interest advocacy: mobilise public opinion, raise awareness, advocate for marginalised groups and apply societal pressure.

- Academic and research institutions: provide critical, independent analysis and frameworks to guide ethical development and counter corporate interests.

- Labour and workforce power: protect workers’ rights, ensure fair labour practices and mitigate job displacements.

- Market competition and innovation: encourage innovation in ethical products and services, foster competition that pushes for more responsible industry practice.

- Media and whistleblowers: inform and mobilise the public and policymakers, act as a watchdog for corporate behaviour.

- Spending and investment: influence the development of technologies, promote innovation, shape the market, strengthen other ecosystem actors.

- Corporate governance: determine the rules that shape decision-making structures within a corporation, set common ethical standards and best practice across the industry.

What is holding back progress?

Workshop participants highlighted that sources of countervailing power do not emerge or operate in a vacuum. For each force making strides in one direction, there is another opposing (and often more dominant) force set on impeding progress. This paints a complex picture defined by power relationships often in tension or conflict. Examples of such tensions discussed include:

- government being impeded by economic and/or political trade-offs, such as its current growth-at-all-cost mandate

- regulators delicately negotiating political agendas and interests

- civil society being held back by limited financial and political capital

- media and whistleblowers being quashed in the face of aggressive non-disclosure agreements

- research and academia’s power being weakened through increasing influence of corporate agendas who control access to compute, data and code

- market competition and innovation power being compromised by vertical integration business strategies, where companies own and control entire supply chains

- corporate governance power relying on political institutions and legal architecture, which can have narrow, exclusionary scopes.

Within the workshop, 2 common themes were identified as barriers to progress for all countervailing power sources in JRF’s list.

Transparency

Workshop participants agreed that all sources of countervailing power are limited by a lack of transparency that cuts across the AI ecosystem, creating asymmetries of knowledge, information and power on multiple fronts. What we do know – and crucially what we do not – about AI is controlled by tech firms, and so much is hidden. From the data that AI models are trained on, to understanding Big Tech’s influence on government, academia and start-ups, many AI companies are ‘open’ in name only.

At the workshop, some questioned the inclusion of government in the list of countervailing powers, arguing that it too is failing to act with transparency when it comes to AI. Despite developing an Algorithmic Transparency Recording Standard designed to ensure public sector organisations are ‘open about how algorithmic tools support decisions’, progress to publish records has been slow. Last month, a new batch of records were released, taking the repository’s total from 9 to 23. While this is a step in the right direction, there is still a gap between the level of transparency needed to build trust in AI and current publication rates.

It can often, therefore, be left to civil society organisations and the media to reveal, where they can, what government is keeping in the dark – most recently, that claims for advances on Universal Credit payments are being examined within DWP by a biased AI fraud-detection system.

Many sources of countervailing power hinge on their ability to pierce through the veil of corporate opacity – investigating stories, empowering whistleblowers, protecting workers, or investigating anti-competitive behaviour. Yet, as Big Tech firms (and the Government, who procures from them) continue to operate under a cloak of secrecy, the work to challenge corporate power becomes ever harder.

Resource constraints

In a powerful statement, one workshop attendee reminded us that the market capitalisation of Big Tech companies is greater than most nation states.

The inequality of resources between Big Tech and countervailing power sources is unlikely to lessen. However, we heard from many how resource constraints within the countervailing power ecosystem itself create further challenges.

Academics discussed how they can suffer doubly from a pressurised ‘publish or perish’ environment, alongside the AI industry’s growing control over the direction of research through monopolising resources and funding. Whilst public funding for AI research does exist, it often focuses on research development stages over exploitation phases (the process of using results in society). How the research is applied in the real world is still driven by a private agenda, which prioritises profit over public good.

Funding challenges are felt acutely in civil society, where we see the age-old story of resource constraints and lack of funder coordination fuelling competition, fragmentation and inefficiency. Those with expertise in trade unions spoke about also struggling to raise significant funding to leverage their ideas; this perspective was shared by participants from independent media outlets, particularly if they are working with whistleblowers.

In the UK, this lack of funding into alternative AI projects that challenge abuses of power is notable. Overseas, however, funding is being leveraged to challenge the harmful impacts of AI, shape coordinated and evidence-based policy action and sustain movements. The European AI and Society Fund, consisting of 14 partners who have pooled funding, supports over 40 civil society organisations with over €8 million to shape AI to serve people and society. In 2023, former Vice President Harris announced a coalition of top philanthropies who had committed to distribute more than $200 million of grant funding to AI projects supporting democracy, innovation in the public interest, workers’ rights, transparency and accountability.

Despite having a smaller philanthropic sector than the EU and US, there have been no similar initiatives from UK funders and foundations to collectively galvanise a diverse AI ecosystem to build power. While conversations about AI, wealth and power are slowly emerging, little resource is flowing to more progressive ideas to challenge corporate hegemony.

Where are the opportunities to act collectively?

Building coalitions for change

A key takeaway from the event was the need to view AI as a complex ‘whole system’; this must include an interrogation of power dynamics. JRF’s workshop aimed to provide space to discuss how certain countervailing forces fit into the whole, think through the connections and interdependencies between them, and identify any opportunities to act collectively.

As American community activist and political theorist Saul Alinsky said in his book Rules for Radicals:

“Change comes from power, and power comes from organization. In order to act, people must get together.”

As such, this convening of people together is a small step towards greater ambitions of a more coordinated and coalitionary ecosystem, strengthened over time through relationships, ideas and action.

Workshop participants reflected on the connections and synergies between different countervailing power sources; some of these are depicted in the Venn Diagrams below. They also discussed opportunities for such coalitions to build shared agendas including:

- storytelling, amplifying civic perspectives, generating public discourse

- investigating and exposing poor industry practice, pushing for shareholder action, strengthening existing institutions and laws

- reimagining an independent research agenda, providing alternative views of AI in society

- inputting worker voice into the entire AI value chain, advocating for worker and consumer input at strategic levels

- pooling investment to build partnerships, subsidising risk, expanding access to resources

- pluralising decision-making, enhancing collective intelligence.

Learning from past wins

Building partnerships is not a new approach to social or political change, and there are many examples to learn from. At the workshop, the Online Safety Act (OSA), passed into law in October 2023, was highlighted as one such example. Here, a range of civil society actors, amplified by the media, helped shape regulation. This led to broad public support for the Act, which obliges digital platforms to make significant changes to their operating models.

Reflecting on key ingredients that successfully landed this legislation, one workshop participant felt that it was crucial to be asking for something simple and specific, helping to root it in a manageable comparison with other sectors. In the case of the OSA, it was ‘do no harm/impose a duty of care’.

There are undeniable parallels between developing the OSA and the current AI landscape dominated by tech-driven narratives and lobbying. There are also similarities between the past and current sense of powerlessness that ‘nothing can be done’.

However, crucially, the ‘do no harm/impose a duty of care’ approach was easy to understand, allowing a broad base of civil society groups with different interests to rally behind it, framing individual campaigns that pushed towards a collective goal. The coalition included voices from groups supporting children, bereaved families, online and sexual abuse survivors, fraud and scam victims, alongside organisations tackling Violence Against Women and Girls and mis/disinformation. And while the resulting policy is not perfect, there are learnings for how a simple and understandable goal, grounded in the experiences of many, helped move several otherwise disparate interest groups to work together.

Narrative and framing

But what is the equivalent simple goal, or ‘ask’, relating to AI that could unite a cross-sector coalition of countervailing forces? According to those that attended our event it seems, at present, that there isn’t one.

It was felt that this is maybe partly because ‘AI’ is so amorphous, and it can be difficult to agree what exactly we are talking about. In this sense, AI is a technology deeply entwined with narrative. Within AI debates we are consistently exposed to an array of powerful analogies, comparisons and metaphors for AI systems, which shape innovation, inform research into AI’s impacts, set the regulatory agenda and frame the policymaking process.

AI’s complexity, however, has not stopped certain actors finding a story and sticking to it. We heard from many attendees how Big Tech firms are incredibly disciplined in their messaging – AI is a ‘machine’, an ‘assistant’ or ‘co-pilot’, a ‘learner’, an ‘engine of growth’ or ‘a tsunami of change’ that can ‘break boundaries’, ‘augment intelligence’, ‘mimic human thought’, ‘drive growth and innovation’ and ‘generate public good’. Other people echoed how the Government has also adopted many of these messages to support its growth-driven agenda. Science and Technology Secretary, Peter Kyle, has likened AI to a ‘moon race’ and thinks we must treat Big Tech firms like ‘nation states’. Prime Minister Keir Starmer described AI as an ‘unprecedented opportunity’ when launching his Plan for Change and, in agreeing to adopt all 50 recommendations set out by Matt Clifford in his AI Opportunities Action Plan, has now instructed every member of his cabinet to make AI adoption a top priority.

Outside of government and industry, the message is less clear. It was agreed that across countervailing power sources, there isn’t a coherent framing on which types of AI are important, and why. A simple articulation of the problem, and a simple ‘ask’ to solve it is lacking. This makes it much harder to build a united and effective movement, empowered to shape public discourse and political debate.

One person explained that while the public has mixed views on AI, any ongoing anxieties linked to these technologies haven’t turned into an alternative narrative to feed campaigning, lobbying or reform. Herein lies the opportunity: how can we collectively frame the problem with AI that motivates people to think across contexts, bringing different sources of power together? What narrative would motivate people to see this problem as part of who they are?

At the workshop, there were various suggestions of such golden threads: perhaps it makes most sense to frame AI through its impact on people as workers? Or is it better to generate a narrative that centres on AI’s impact on people as consumers? Or should we produce messaging on AI’s impact on people as data generators? What would be the ‘ask’ for each of these examples?

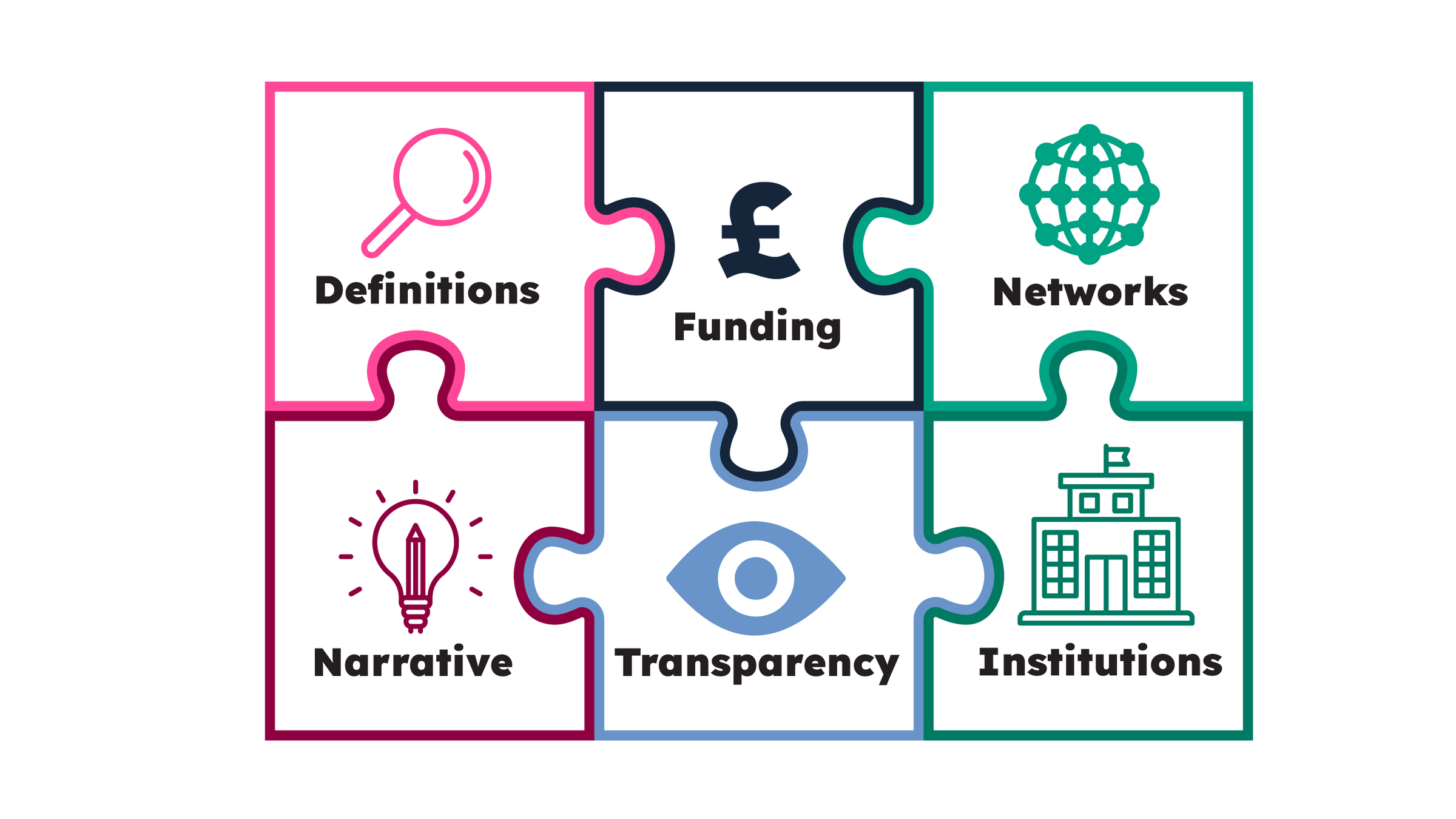

This is a defining takeaway from workshop discussions; nailing down the narrative, and the ‘ask’ that flows from it, is the first step towards building a coalition of countervailing forces who can act together.

What should happen next?

We asked workshop participants to reflect on 2 final questions:

- What is the one thing that needs to happen after having these conversations?

- What is the one action I will take to help things progress in some way?

We’ve grouped responses thematically to provide an overview of the ideas the group put forward, giving a sense of where we left discussions.

Define the challenge

Move from nebulous language and get specific about the aspects of AI or Big Tech that need countering, by defining a shared harm or problem.

Develop the narrative

Create a cohesive narrative of this problem and ensure discipline in messaging. What could be a coherent ‘ask’ for the upcoming AI bill?

Build out networks

Develop alliances through joining up the intersections of our current individual and organisational networks. Power comes from connecting people together and engaging in collective thinking.

Design the institutional response

What is the state’s role in better supporting a countervailing political economy? For example, could they establish a Digital Civil Society Observatory? Who can expose political influencers to this way of thinking?

Push for transparency

What tools do we have available to push for greater transparency in AI? Who is best placed to do this work and how can we strengthen their activities?

Fund the ecosystem

Resource is needed to build on these conversations and flow towards progressive ideas and action. Resource-holders, from philanthropic foundations to the Treasury, should consider how their funding builds the strength and capabilities of an ecosystem and incentivises partnerships.

This reflection is part of the AI for public good topic.

Find out more about our work in this area.