Relational public service can tackle hardship in neighbourhoods

Changing our public services to focus on relationships and learning will help both people and communities to thrive.

Neighbourhoods with high levels of hardship have multiple and complex problems. These can apply to people or the place, and are often interdependent, for example poor housing and transport links, degraded environments, high levels of crime and fear of crime, low levels of employment and low incomes, low educational attainment, and problem substance use.

People’s lives and places are complex systems, which can be understood better by seeing them as sets of relationships, made up of contextual factors and the actors within. The failure of public services to understand and respond to these relationships hampers their ability to support people to move from struggling to thriving.

What are relational public services?

Family and community are often people’s first port of call when they hit tough times. But there are occasions when the care someone needs may not be available in their current relationships, or they are alienated from the communities which can act as support.

This is where relational public service comes into its own. This is an idea that has been heralded for some time, for example going back to the Scottish Government’s Christie Commission Report of 2011, but has proven challenging to pin down in practice.

There are 2 key elements in our view. First, it is about a mode of interaction. Public service should start with workers building meaningful relationships with people, as people. That means understanding their particular strengths and what matters to them. Second it is about positive relationships being a key part of what public service is seeking to achieve. Relationships are not just a means to an end, they are necessary aspects of human thriving. Relational public service offers forms of relationship which may be initially absent - or underdeveloped - and can help someone to build a web of nurturing social relationships over the long-term.

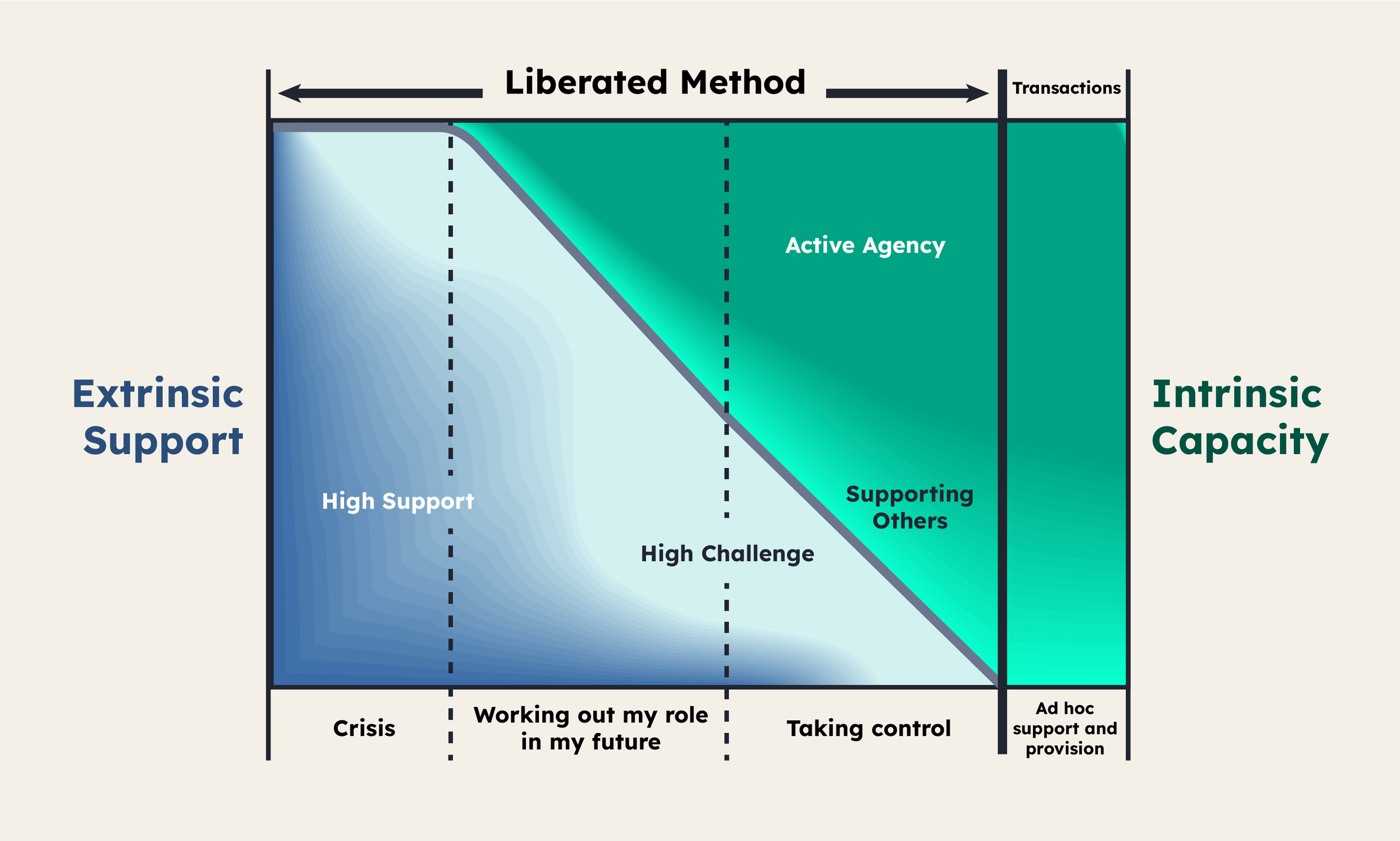

The Liberated Method, developed by Changing Futures Northumbria, is a good example of these ideas in action. It takes a caseworker approach, with a high-support high-challenge relationship rooted in trust. Trust is initially built by being present, attentive, pragmatic and effective at dealing with quickly solvable issues (such as sorting out benefits). Longer-term goals related to behaviours and strengths are worked on once trust is established. Crucially, the caseworker only has to adhere to 2 rules: to do no harm and do nothing illegal. Otherwise their work is guided by principles, such as understanding rather than assessing people, and pulling support to people rather than referring them on. It is an approach that has enabled people to thrive who have experienced the most challenging combinations of problems associated with homelessness, mental ill health, substance misuse and involvement with the criminal justice system.

But the work also shows the support of public service workers can only take people so far. Once people’s lives have become a little more stabilised and they begin to see hope for themselves, connection to other people in their communities becomes critical. These are frequently place-based communities, but can also be based on other shared stories, such as life passions, sexuality, gender, ethnicity or belief. This diagram represents learning from across a range of Liberated Method cases. It highlights the role of public service workers in using their ‘extrinsic support’ to help people over time to develop their own ‘intrinsic capacity’ to lead a thriving life.

In this context, the role of public service is therefore to act as a guaranteed care relationship. Relational public service provides people who need help with a supportive, constructive relationship when others can’t or won’t (for whatever reason) assist them. It then helps people find relationships within their community that enable them to thrive.

This is not the only role for relational public service. It can also help to support relationships between people in communities. These include forms of community development activity, such as the Plymouth Octopus Project or Coast & Vale Community Action or peer-to-peer mental health support, such as the Moray Wellbeing Hub or Recovery Colleges. This work is often funded through a mix of state and other funding, but can be nurtured by a supportive local state.

In this context, relational public service seeks to develop the care capacity of all relevant communities, what we might think of as seeking to build universal community relationship infrastructure. No matter what community you identify with, it should have the capacity to offer care. Achieving this goal will help ensure that the guaranteed care relationships provided by the state are needed as infrequently as possible.

We should be striving for public service that provides bespoke support to help people take steps forward in their lives, while simultaneously strengthening the social infrastructure that helps create and maintain relationships between people in neighbourhoods and other forms of communities. That would indeed be a social safety net that protects people from hardship.

How to make relational public service real

Even more elusive than what relational public service looks like has been how it can be planned, resourced and managed. This requires us to address the structural impediment created by the dominant approach to public management, New Public Management (NPM).

NPM significantly hinders relational public service in two ways. First, by its use of standardised, top-down performance metrics it reduces the scope for bespoke care. Second, by breaking the learning relationships which underpin such care through the use of competitive tendering. Such practices disincentivise learning between organisations, corrupt the data required by public service to learn and adapt, and break long-term relationships between practitioners and residents by creating provider churn.

Fortunately, public managers now have a choice about how to undertake the task of public management. The Human Learning Systems approach enables those whose job it is to organise the provision of public service to do so in a way which supports the development of learning relationships between public servant and resident, and by focussing leaders’ attention and accountability on the health of the complex systems from which positive outcomes emerge.

There are now over 50 case studies providing examples of a Human Learning Systems approach to public management in action. There are even national government-level change programmes beginning to emerge, such as the work of Healthcare Improvement Scotland. If we want to enable public service to tackle hardship, it is within our grasp. By changing the purpose of public management to focus on learning relationships, we can create the necessary conditions to effectively tackle hardship in neighbourhoods.

About the authors

Toby Lowe is Visiting Professor at the Centre for Public Impact and Senior Lecturer at Northumbria University.

Mark Smith is Director of Public Service Reform at Gateshead Council and a Visiting Fellow at Northumbria University.

This idea is part of the neighbourhoods and communities topic.

Find out more about our work in this area.